Live Animal Export: Monitoring sheep for the long haul

In 2015 Australia exported 2.01m sheep, 12,560 (0.62%) died and were thrown into the ocean. Cruiseships don’t operate like this. Dr Lynn Simpson is back with her 15th installment for Splash.

In the words of Martin Luther King Jnr, “The time is always right to do what is right”.

Wonderful saying, sadly one that is not always achievable on a live export ship.

Monitoring sheep on a ship is like playing ‘Peek-a-Boo’ at sea.

The stockmen, crew and vet spend their days looking for any health or management issues that require attention.

Any issues found will be triaged. Classified as action required ‘immediately’ (trapped, badly injured or terminally ill animals), ‘today sometime’ (overly crowded pens needing adjusting) or maybe just to be flagged in a report for future reference or remedy by the regulators, shipowners or exporters (minor mechanical, infrastructure issues or rejects found on board; pink eye, salmonella, shy feeders or heavily pregnant animals).

The World Organization For Animal Health (OIE) has a welfare code for the transportation of animals by sea. It states that there should be:

“ability to observe animals during the journey- animals should be positioned to enable each animal to be observed regularly and clearly by an animal handler or other responsible person, during the journey to ensure their safety and good welfare”

Great concept, rarely the reality, on sheep ships, and poorly achievable on double tiered sheep decks. It’s often during the final unloading of a sheep ship where you get to see some animals for the first time. Sheep hide many health issues well, not wanting to look weak, susceptible. Hence during unloading I would walk around the decks and euthanize any animal whose true disease condition was not detected during the voyage. Usually blind sheep, or severe lameness or horrible infections from shearing cuts. And of course any babies found; left behind as their mothers are unloaded. Kill, kill, and kill.

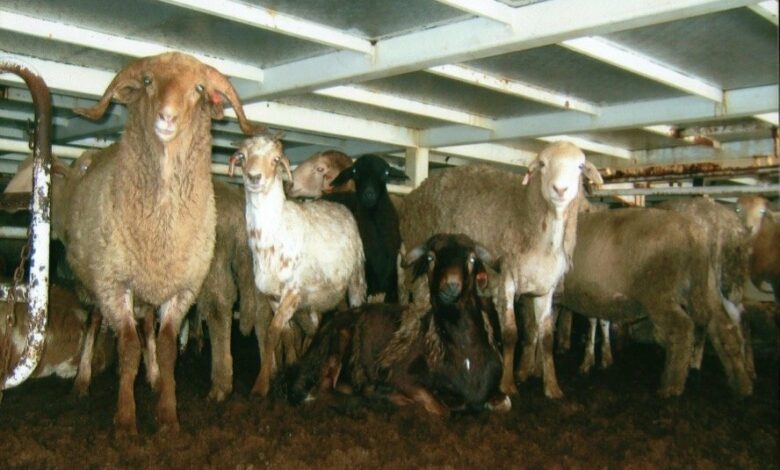

Detecting health issues can be as simple as walking around a loosely loaded deck; loaded below regulatory maximum stocking density as shown below. This is a rare occurrence. I’ve still had to climb to see these sheep, but as there is extra space, many animals are lying down. Luxury. This enables me to see more animals beyond them to assess their health status. Clear as mud really.

This lower stocking density happens occasionally; if numbers required to fill a vessel cannot be found due to drought, health or pricing issues. The mortality outcomes are usually lower, indicating improved health.

The other times we ‘light load’ is if the exporter is being ‘punished’ for a previous high mortality voyage and then there is often a 3 voyage, 10% lighter loading penalty to ensure a better outcome.

Unsurprisingly, the light loaded voyages generally have improved ‘performance’, indicating that this is better for the animals, less deaths. Unfortunately this isn’t enough evidence for the regulator to consider changing this loading density to be the permanent one, we then load ‘fully’ again and things continue as usual until another high mortality outcome.

2% of our passengers can die before any regulator raises an eyebrow and considers the number unacceptable. Arbitrary at best. Cruiseships don’t operate like this.

Fully loaded ships are harder to monitor, especially double-tiered sheep decks. A never-ending ‘Groundhog Day’ of repeatedly inspecting all animals loaded.

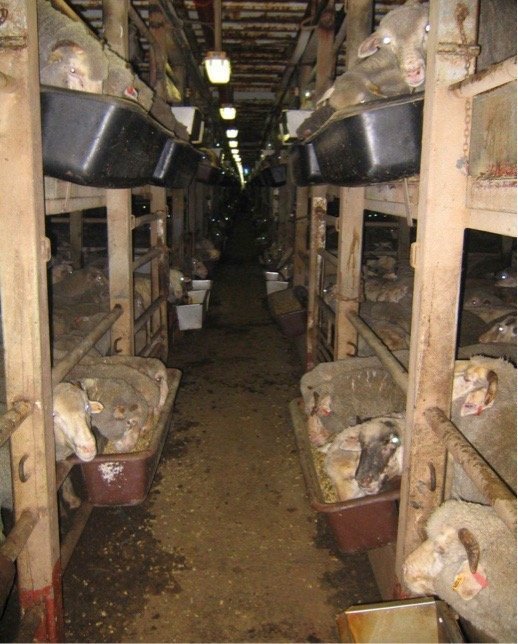

Double-tiered sheep decks are hardest, the health status of sheep in these pens is often guesstimated based on the condition of the individual animals at the front of the pens. These front sheep are usually the strongest and healthiest animals as they have jostled through the crowd to the prime position of being near the feed and water troughs.

The shy and potentially unwell animals will be at the back of the pen, or lying down somewhere in-between, obscured from sight by their pen-mates. These are the ones we need to find, but are often illusive and found dead.

Double-tiered ships are designed so the upper deck flooring is at a height of about 1.5 m, hence most stockmen, crew and vets spend much of their days stooped, using torches, peering into the rear of these pens. Chronically painful for monitoring, frustrating and inadequate.

The upper decks have all the feed troughs along the front above this 1.5 m region, hence at the average persons head height.

This means upon inspection from the alleyway the front animals knees can often be seen and the tops of their heads as they use a trough. Everything else obscured. Gateways provide small windows into the pens, but the sheep near the front obscure the rear sheep; becoming sheepy barricades.

To get a proper view, one must climb on the often slippery, tubular rails from the lower pens and take as good a look as you can. The image below has the troughs lowered, as approximately 20% of these young sheep couldn’t reach the troughs. The trough should be hanging off of the rail above their heads. I still stood on a raised railing, 2 foot off the ground to take this image.

Hence when working double-tiered ships monitoring is reliant on stooping, climbing, glimpsing between legs. This leaves lots of guesswork and does not provide acceptable confidence in the true health status of all the animals onboard.

Every day the crew must climb in, do a shuffled stoop throughout these short areas, dodging frightened, running and jumping sheep. They are looking for sick, injured or dead sheep, but often get injured themselves. It’s an unenviable and dangerous job.

In 2015 Australia exported 2.01m sheep, 12,560 (0.62%) died and were thrown into the ocean. In 2014 Australia exported 2.24m sheep, 15,899 (0.71%) sheep died and were thrown into the ocean. Deaths in the feedlots before and after sailing not included.

FYI: The average 4-deck semi trailers people are used to seeing on the road carry about 450 mature sheep. Do the math, seeing one livestock truck rollover and the subsequent injuries and deaths upsets the average person.

At sea we don’t see them dead on the road, we watch as they float past in the ship’s wake.

The inability to identify all ill animals is why we often have to ‘blanket medicate’. This means we see traces of illness; diarrhea on the ground, on a railing, in a trough, but we rarely know who it came from. So soluble medication is placed into the drinking water for diseases such as salmonella. Quite ineffective, poor veterinary practice and simply results in drug residues in the meat to be consumed from these animals upon arrival in their destination countries if not feed-lotted long enough. I try to avoid it.

As these voyages progress the animals get more fatigued, possibly ill/ less scared of humans. This combination makes determining a sick animal from a well one more difficult as its often their reaction time to our presence that we rely on to determine vitality. Often 100,000 sheep or more are monitored by only one vet and one or two (if lucky) stockmen.

A long haul voyage to somewhere like the Middle East can result in animals barely looking at us as we wander along.

Are they tired, are they sick, you’ll know the next day if they are dead.

For Lynn Simpson’s full archive of shocking exposés into the livestock trades, click here.

Thank you for giving numbers. The numbers are not all that bad. A little research tells me that the average sheep mortality in Ireland is between 5 and 10% per year which comes out to 0.1 to 0.2% per week. (http://www.banbloodsports.com/sheep.htm)

0.62% is certainly higher but not astronomically higher. (I realize that Ireland is not Australia, but the Irish statistics were easy to find.) I assume a voyage lasts about a week. So a sheep is ~4 times more likely to die on board a ship as in a pasture.

I expect that sheep that are exported as breeding stock are shipped differently, so the sheep you the ships you describe are going to be slaughtered shortly in any case. That puts a certain light on their suffering. Not that there is any reason to be cruel to animals even in the last week of their lives.

All I can suggest is to carry on, and remember you are helping to feed people, many of whose parents and grandparents could not afford to eat meat very often.

“Not that there is any reason to be cruel to animals even in the last week of their lives” ….that simple sentence completely destroys the live animal export trade, and is the only thing Gary said with which I can agree…the rest of his comment is complete nonsense.

Dr Simpson is a leading advocate against the live animal export trade.