Livestock cooked alive at sea

In the fourth of a searing series for Splash, leading Australian livestock expert Dr Lynn Simpson explains what happens when things get too hot below deck: “like a cross between a Sunday roast and roadkill”.

Unbelievably, some animals literally cook to death as we sail on live export ships.

When I started sailing in 2001, I ate all meats. After too many heat stress affected voyages I cannot stand roast sheep, disappointing many a farmer host. There is very little difference in my view to slow cooked meat and bodily decomposition post death.

I don’t need to watch cooking shows, I’ve watched it happen on the hoof.

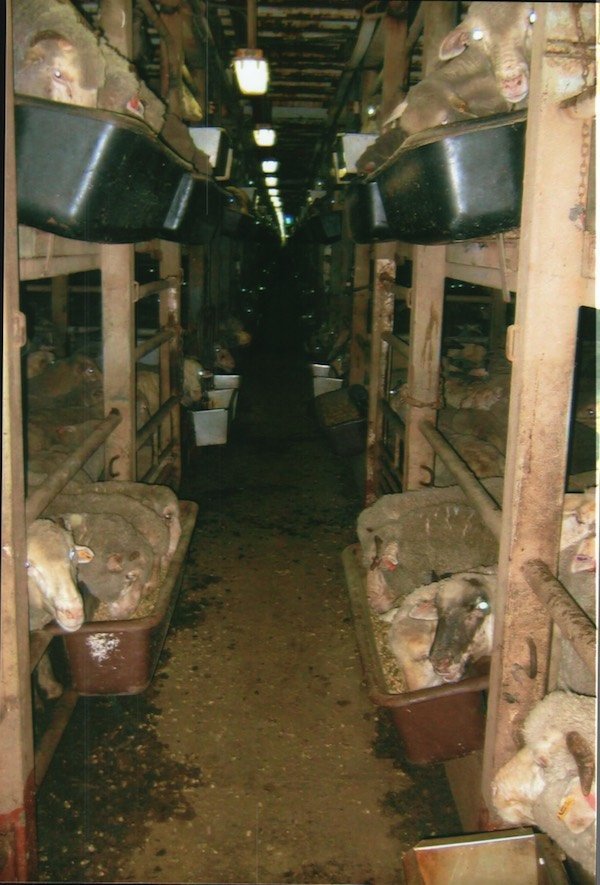

This risk on live animal export vessels is greatest during mid-year when we (Australia) take winter adapted animals to the northern hemisphere summer. That time is now. Our cargo (sheep and cattle) can literally cook to death from environmental heat stress when our wet bulb deck temperatures exceed 30 degrees Celsius and the humidity is in the high 80s and above and or if they have existing diseases such as pneumonia as with the picture of the dead bull with the foaming nose; a classic sign.

Humidity is the killer. We could be in Kuwait in 50 degrees dry bulb temperature, but low humidity (below 70%) and things are fine.

Once that wet bulb creeps up, we are in trouble.

Sheep appear more vulnerable. Is it the double-tiered decks, the stocking densities, the fact that they wear wool? Or all the above? Probably a combination.

When we sail through notorious heat risk areas such as the Gulf of Aden, the Straits of Hormuz or the Persian Gulf everyone onboard is on heightened alert for the signs that we may be minutes away from a mass mortality and animal welfare disaster. The deck crews watch closely, the vet and stockmen pace around trouble spots and the navigational officers watch the cargo keenly from the bridge windows if possible. Everyone’s radios are on the ready.

The very minute signs appear everyone jumps into action.

The signs include animals literally gasping for breath with their tongues out, quickly turning blue from lack of oxygen. Respiratory rates are in the two hundreds per minute. Too high to reliably count with the human eye. The air fills with toxic levels of ammonia and CO2 as it depletes of oxygen. And it’s bloody hot!

Any ship nearby must think we have developed either a drinking or a steering problem as the bridge and the engine room coordinate quickly to begin ‘swinging the ship’. This appears on other vessels’ radars as if we are zigzagging. We literally turn the ship sharply to try to catch some crosswind and flush the buildup of toxic gases from the open decks and replenish them with fresh air full of life giving oxygen. We then turn back and repeat this at approximately 15 minute intervals until the cargo begins to show signs of relief, or the wind picks up and takes over. If really bad, we turn 180 degrees and sail into a following or stern breeze. If we are in narrow sea traffic lanes or there is lots of sea traffic around us, we are stuffed. Animals die before a ship collision would occur.

The captains on these vessels show great courage at these times.

A higher risk is whilst unloading in some ports, when zigzagging is not possible. In these times we have tug boats on standby in case the situation gets unbearable and we have to stop unloading our cargo and rush back to sea for fresh air, hoping it happens in time to save lives.

Other mitigation strategies include not feeding animals in the hours preceding highest calculated risk, reducing their internal temperature. Removing any barrier to crosswind such as feed troughs.

When a heat stress event occurs all hands are on deck immediately, the ship swings and all barriers possible are removed. The animals usually exhibit the extension of their necks out over the railing desperately seeking oxygen. Their bodies heat up from external environmental heat and internal friction of breathing. The heart increases beating as the affected animals dehydrate, their poorly oxygenated blood gets thicker and harder to move around their bodies.

They begin to compete for air supply vents, the strongest climbing on the weakest for air clearance. As they weaken they collapse, lose consciousness and soon die. The normal body temperature of a sheep is around 38.5 degrees. One day we had an entire deck behaving as described, we were losing them. They were dropping around us like they had been shot in the head. Except there was no bullet. As they hit the deck we would drag them out and I would cut their throats. One day as I was cutting heat stressed throats for mercy kills, I had a strong spray of blood from the throat scold my wrist.

Brain damage in humans is a concern if the body temp gets above 41 degrees Celsius. I was sure these animals would never recover once collapsed, and I feared the survivors would die slowly within a week from kidney failure. Kill, kill kill. The next sheep I cut I also used the deck thermometer to measure his core body temperature. I was blown away to find it was 47 degrees Celsius. About the same temperature of the average household hot water system. Their fat was melted and like a translucent jelly. They were cooking from the inside.

As such their muscles were discoloured. They were decomposing in front of our eyes. This is a grisly task for all on deck. The crew are already risking their lives working in such a toxic environment. Safe working ammonia levels should never exceed 25ppm. These were far exceeded. Then we are all expected to begin removing the dead bodies and throw them into the ocean. If this process is delayed the job gets harder and more disgusting. Legs literally pull off as you try to drag them and they simply fall apart. You have to make haste with the waste.

And the deck smells like a cross between a Sunday roast and roadkill.

To access Lynn’s other articles for Splash, click here.

Dear God. What satanic humans do this, knowing what we now know? Thank you so much, Lynn.

Dr Simpson has highlighted some of the challenges that face the Live Animal Export Industry, world wide.One only needs to read the Splash 24/7 regarding the problems at sea that livestock carriers experience. The problem is that they don’t say that most of these vessels have been banned from the Australian waters as they don’t meet AMSA standards or the like, and they are managed and run by ‘Hillbillies’

What is interesting is that its is not the livestock transport industry that is the problem but the way it is done and by whom.

If the industry is conducted within the rules and regulations set out in Australia by the Maritime Regulators, AMSA [Australian Maritime Safety Authority], ASEL [Australian Standards for the Export of Livestock] and ESCAS [Exporter Supply Chain Assurance System], then the industry seems to run well. Extremely well in fact. We never read about the 98% successful events that occur on a daily basis and for the last 30 years.

Yes I agree with Dr Simpson that there are areas and seasons, in the world, where and when, we must take great care when we travel through them with animals aboard eg The Somali Straits, Straits of Hormuz, Red Sea, Persian Gulf.

The weather and humidity can be stifling and life threatening. These conditions must be, and are, managed by the experienced people. It is no different to an Airliner flying through volcanic ash. Manage it or better still avoid it. Don’t stop the industry.

If you are going through these areas during the northern summer here is what you should do:

– decrease the loading density of the pen, thus spread your animals or don’t load to capacity.

– zig zag the course so that the envelop of humid air is always dispersed

– Pass by at night

– dont take unsuitable animals, eg Bos taurus cattle or British breed sheep, try the fat tail breeds and Bos Indicus cattle.

– Use ships with adequate ventilation, and supplement it where possible, eg external fans, air vanes, open ramp doors

– Above all plan the trip and the time of arrival in these areas.

Now this may sound simplistic but we used to do it!! Yes, the weather in Kuwait may be 50 degrees Celsius with very high humidity, but it can and has been managed previously and into the future.

The industry is to be based on:

– Modern, well designed ships with adequate ventilation. Where possible with directional variation either, over the animals head region and separate alleyway air flows.

-Low density loading of pens in the Northern Hemisphere summer.

– Bos Indicus cattle and Fat tail sheep or similar breeds.

– Clever management based on animal welfare and good shipping knowledge, ’sheeping and shipping at the same time’

IT DOES WORK.

Im getting rather tied of Dr Simpson’s photos and complaints:

– Comparing the industry to the slave trade

– faecal contamination

– cooked sheep

– individual dead cattle frothing from the nose and so on.

She is very anthropomorphic in her writing and criticism.Her writings are lean on professionalism and heavy on drama.

These comment are all critical of an industry she dedicated 10 years while undertaking 54 voyages. What was she on about?? Wasn’t she in charge of Animal welfare?

On my last voyage to Russia ,aboard the MV Nada, we travelled through the Great Australian Bight in force 4 gales,and through the Straits of Hormuz, with extremely high temperatures and humidity, in May/June. Of the 17499 head of Angus Cattle, 2500 approx were pregnant, 23 died, most from mis-adventure, [fighting etc] and 4 females aborted.

I could have photographed these, and highlighted the decomposing bodies trampled overnight by the others in the pen, with skin off and frothing from the mouth. I could have lined up the four aborted foetuses side by side and sent this photograph around the world.

These deaths were true but the reality and context was different: 17499 cattle arrived live, well and with an over all weight gain.The 2400 odd pregnant angus heifers and cows didn’t abort and I am sure calved happily on Russian farms a few months later.

THAT WAS THE REALITY.

Its is hard to calculate the benefit this voyage had for all those involved from bankers, suppliers, fodder manufactures, shipping personal, exporters, importers, Russian farmers and the ultimate consumers.

Let us stay focused. Don’t criticise unless you know.

The industry is based around simple Animal Husbandry principles of :

-The right animal, loaded on a well designed modern vessel, with more than adequate ventilation, loading suitable numbers at acceptable densities, at the right time of the year, being fed, watered and cared for by experienced people, protecting them from the anticipated weather elements.

Managed well it is a great industry that benefits many.

– Dr Peter Arnold, BVSc MSc. Veterinarian, 50 years experience in Live Animal Export (peterjarnold1@bigpond.com)

Dear Peter,

Thank you once again for taking the time to read, analyse and comment on the latest piece in Splash 24/7 regarding my shipping experiences.

I sense you have great frustration regarding this trade and its fluctuations, and as someone who contributed to the Senate Select Committee report tabled in Parliament in 1985 I can see why this still troubles you. Your recommendations for reform and improvement for animal health and welfare were sound.

– Ship deaths in first 3 days related to feed-lotting not vessels

– Inadequate shelter in feedlots etc

http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Significant_Reports/animalwelfarectte/exportlivesheep/index

It is also now clear to see that your attempts at educating the committee and recommendations from that time have not been embraced by industry or the Government.

I share your frustration with this. Anyone interested can of course open the link above and read the recommendation summaries on pages xiii, xiv, xv,xvi, and xvii.

Many of these issues are still causes of great concern today and are directly resulting in livestock mortalities.

Thank you again for pointing out that livestock mortalities are at 98%. What the public and I would like to know is, what are the true figures for livestock morbidity. Mortality being dead, morbidity meaning unwell, injured, ill. Mortalities are easier to quantify and detect, but are a blunt indicator of the success or not of a voyage, or export process from start to end. Of course the 98% does not include any mortalities from land transport, feed-lotting and recovery from the cumulative live export voyage stress in the importing country.

I agree that technically we can export any animal anywhere in the world safely. Great examples include the Melbourne cup runners each year, pets and international zoo animal transfers. The problem is, with our primary production animals we do not. Why?

I suspect as two seasoned animal welfare professionals who have tried to improve legislation we both feel frustrated. I shall continue to share my experiences, and I welcome your feedback. FYI: all the vessels I am writing about are still trading out of Australia.

Sincerely

Dr Lynn Simpson

Just when I think human beings can’t get more evil and cruel,I read this. As someone who realizes animals are living ,breathing creatures who feel pain,and fear and suffering. Who want to live ,who love their babies,who are capable of giving such great love and companionship back,Whom God loves. To treat living creatures this way is a sin, and a crime against everything good, and decent,and just. I live everyday of my life without eating ,wearing,abusing,or hurting any animals in any way. Believe me ,it is possible to do the right thing. One day at the end of your lives,when you look back,you will realize what you have done,and the very impact of what you have done to living beings. Just plain shameful!