Oil in the Arctic: Do we sustain the environment or ourselves?

Rachel Finch from Tuscor Lloyds looks at Norway’s Arctic oil scene.

The oil industry is now recovering from a heavy slump over the few years, and with the environment remaining at the forefront of policy, you might expect the Arctic to be the last place that the industry is setting out to find new resources.

Prospectors now have their eyes set on the Barents Sea off Norway’s northern tip, with companies Lundin, OMV and Statoil expected to begin drilling up to 15 new wells. Assisting them will be Statoil’s Songa Enabler, a floating drilling machine the size of two football fields. The Songla Enabler is an innovative concept which was developed by the industry for Statoil and the firm will use the facility to drill the first five wells. The Enabler is also designed to be winterised so it can withstand temperature drops of up to -25 Degrees Celsius.

The Barents is a key region yet to be exploited. Its gulf stream means it’s largely ice free unlike Arctic regions such as Alaska and Greenland, places which have been abandoned by oil majors like Royal Dutch since 2014. The shallow water of the Barents means it’s more cost effective, and these projects have huge potential. The fourth well to be drilled by the Enabler will be Korpefjell, which is the largest prospect to be tested since the 1990s.

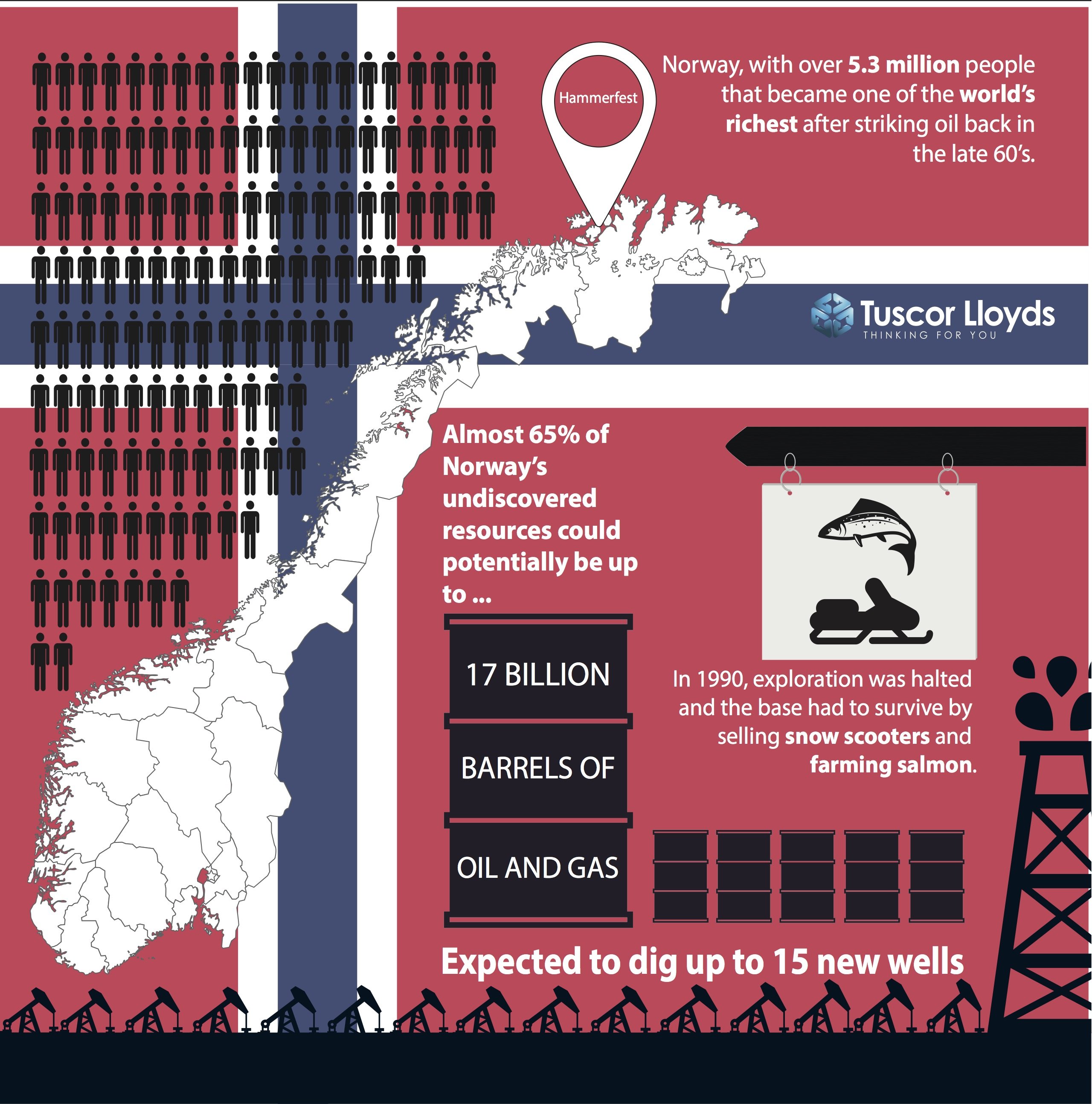

Norway is hoping the unexplored Barents Sea will boost their oil industry, after crude production fell by half since the early 2000’s. The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate has estimated almost 65% of Norway’s total undiscovered resources could be lying in the Barents Sea – equivalent to 17bn barrels.

The regional oil hub is the town of Hammerfest where the Polarbase serves ships supplying the Enabler and other rigs. The current boom in oil is a welcome one for Polarbase. In 1990, exploration was halted and the base had to survive by selling snow scooters and farming salmon. Kjetil Holmgren, manager of the Polarbase has said that they can “now focus on oil and gas”. Despite the slow start Statoil, Lundin and OMV have still managed to extract more than a billion barrels in the Barents Sea since 2010. Last year, Eni started producing oil from Goliat (the area’s first platform). Statoil plans to make a final decision for the investments on the Johan Castberg Project this year as well after reducing operational costs by more than 50%.

The government has proposed a record number of Barents blocks in its next licensing round yet not withstanding industry optimism, Arctic drilling remains a controversial subject. Norway, with just 5.3m people became one of the world’s richest countries after striking oil back in the late 1960s, yet environmental groups still have a strong influence over policy decisions.

Greenpeace and WWF say drilling rigs are going too close to the edge of the polar ice sheet. This could pose a catastrophic threat in the case of a spill. With a fragile ecosystem that sustains thousands of different species from plankton to mammals, a debate is raging over whether oil and gas in the relatively unspoiled Barents is morally justifiable, or commercially viable even as climate change policies cause demand for fossil fuels to plummet.

If Arctic projects don’t go ahead, it could mean billions of lost revenue for the Norwegian government, which offers generous refunds and deductions for exploration and investment in a trade-off for imposing a high tax rate on oil production.

“There’s a very high probability that these investments will be stranded assets,” said Jens Ulltveit-Moe, a Norwegian investor who made part of his $400m fortune in oil-related projects. Statoil and Norway’s Petroleum and Energy Minister Terje Soviknes doesn’t agree.

“With a break-even price of $35 a barrel, we’re competitive and then some,” he said in an interview on board the Enabler, referring to Statoil’s Castberg project. “That makes a lot of the stranded-assets debate disappear.”

Statoil’s Barents Sea wells are among the cheapest in its global exploration portfolio this year, at $25m apiece at most. That’s good news for Hammerfest, where the oil industry has created 1,200 jobs since Statoil decided 15 years ago to build a liquefied natural gas plant to process production from the Snovhit deposit, the Barents Sea’s first field.

The town used to be a run-down place from which you moved away if you wanted to get ahead, said Polarbase’s Holmgren, now 55 years old and from Hammerfest. Now, “young people who leave have plans to come back.”

, a floating drilling machine the size of two football fields. The Songla Enabler is an innovative concept which was developed by the industry for Statoil and the firm will use the facility to drill the first five wells. The Enabler is also designed to be winterised so it can withstand temperature drops of up to -25 Degrees Celsius.

, a floating drilling machine the size of two football fields. The Songla Enabler is an innovative concept which was developed by the industry for Statoil and the firm will use the facility to drill the first five wells. The Enabler is also designed to be winterised so it can withstand temperature drops of up to -25 Degrees Celsius.