Environment over economy key to China’s containerised trade outlook

Chinese industry is key to the global box market writes Sam Williams from ClipperMaritime, a consultancy that has this month launched a newsletter, Container Horizons.

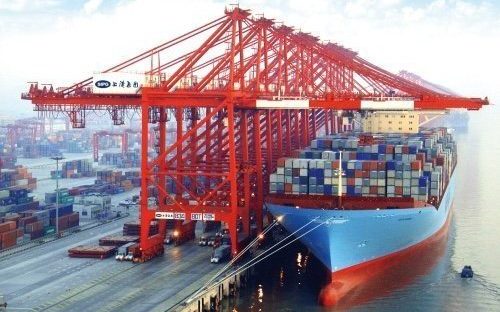

China is the most important market for the global container industry. About 180m teu is handled annually by the top ten Chinese ports, whether for import, export or intra-country shipment. This also includes transhipment and empty volumes.

Since its admission to the World Trade Organisation in 2001, China has become the factory of the world. However, the recent push to reduce air pollution through reducing coal use and emissions from factories could shrink the global footprint as manufacturing moves elsewhere in Asia. Chinese authorities are shutting down factories for inspections or for breaching environmental and other regulations. In the latter case, the plants stay shut for longer. Given China’s importance to all container trades, any slowdown in factory production will depress cargo volumes, at least temporarily. Spot freight rates may suffer as carriers fight to fill empty slots on affected trade lanes.

Collecting reliable and timely data on industrial activity in China is difficult, which complicates the task of directly assessing the depth and breadth of the factory shutdowns. Almost all factory output due for export will move by sea. Our extensive maritime data allows us to investigate how port volumes have been affected by changes in industrial production.

Form the first indications of factory shutdowns in August 2017 to December there has been a noticeable drop in container loadings of around 8%. Of these, exports have fallen around 10%, although this is from a historic high (potentially in anticipation of the factory shutdowns).

At first glance it appears that the factory closures have had an impact, but we need to consider this in the context of usual seasonal patterns in China. There is a usual drop-off in traffic from August to the end of the year as we move past the peak demand season. The trough of the decline in 2017 has been deeper, however.

This drop in container traffic suggests there has been a fall in industrial output, which in turn suggests that factory shutdowns are starting to have an impact. Further insights can be obtained from looking at the data geographically and by cargo type.

Heavy industry in the north has suffered

Chinese ports have experienced mixed fortunes for domestic containerised cargo flows. The northern ports have declined 5.3% yoy, while central and southern regional volumes have both jumped by more than 15%. The seasonal trend shows that China has had less productive months following the shutdown compared to the historical average.

The north is dominated by heavy industry such as steel, coal, aluminium and fertiliser production. These provide the intermediate products used for the production of consumer goods. Unlike export trades, we have recently seen steel and coal being shipped domestically via containers. In the last year, some of the big operators have bought cheap second hand panamaxes that have been available in the distressed market.

The decline in domestic traffic in the north suggests a decline in heavy industrial products shipping south for use in manufacturing of consumer goods. These are the most heavily polluting industries and are where the biggest environmental gains are, so would be the first to be targeted for shutdowns.

Given the decline in heavy industrial production in the north, there is a gap to be filled. Factory inventories cannot last forever, so the spotlight is on more imports and new domestic sources. The jump in domestic volumes in the south/central regions suggest a new route is potentially supplying the centre’s manufacturing requirements. YTD in 2017, the centre has imported 1m teu more than in 2016, up 12% yoy, and we note a 40% growth in teu from India, another prominent source of iron and aluminium.

It is likely many factories will return to production, but should they fail to meet regulations, new domestic and international cargo flows will continue to develop to and from main China ports.

Heavy industry in consumer goods production buoyant despite shutdowns

Compared to 2016, exports are up across all major ports. The central ports have flourished, growing by more than the northern and southern ports combined. The seasonal trend shows that China is seeing a more active November for exports than it has seen historically, following a drop in October. From the port data it appears that the factory shutdowns are not having any impact on exported goods. If anything, factories producing exported goods appear to be more active than ever.

China’s biggest exports include consumer goods – electricals (1st), textiles (2nd) and other manufactured consumer goods (5th). The majority of this industry located in the centre (eg computing, below), and it is highly containerised. The strong growth of containerised exports in the centre suggests that these industries are unaffected by the factory shut-downs, and are in fact flourishing. Iron and steel products (China’s 3rd largest export sector) and fertilizers (6th), are not typically shipped internationally in containers, so we cannot infer any changes in production from container traffic figures.

The increase in cabotage shipments to and from the centre, up by 680,000 year-on-year, points towards growth in the industries along the Yangtze river, which ship goods by barge to Shanghai.

Overall, port traffic strongly implies that consumer goods production in the centre is thriving.

It appears the hammer of environmental regulation has struck the northern heavy industries first, but a second wave of inspections could follow. Southern based factories have been less hit by closures as they are more geared towards the production of fast moving consumer goods.

Very informative article, thank you.