From pirate’s nest to free port

Celebrating 50 years since the founding of the republic, award-winning author Paul French writes exclusively for Splash on the history of maritime Singapore.

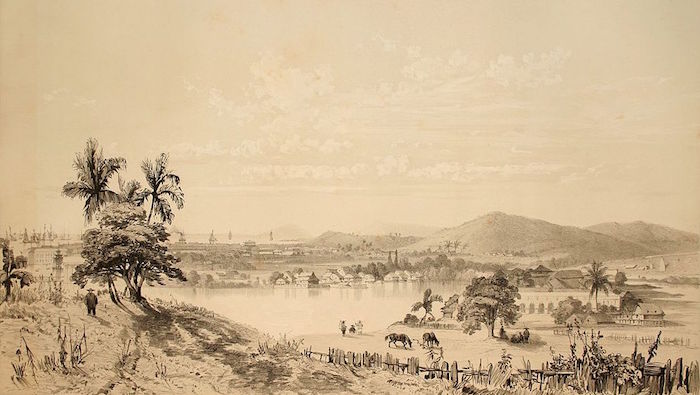

As with so many things in Singapore it begins with Sir Stamford Raffles. Raffles was a visionary and in 1819 he gazed across the naturally deep and sheltered waters stretching between the peninsula that is now Singapore and the small islands of Pulau Brani and Pulau Blakang Mati (better known these days to everyone as Sentosa) and realised he was on the shores of what could be a great port. A captain in the East India Company, William Farquhar, had originally told Raffles of the harbour – inhabited only by orang laut sea gypsies and cutthroat pirates. But it suited the needs of the East India Company and the British Empire perfectly. Raffles claimed Singapore for the East India Company (and by extension the British Empire), made Farquhar the Permanent Resident and ordered Captain Henry Keppel of the Royal Navy to clear out the infestation of pirates. The Port of Singapore was open for business.

However, from the start, the Port of Singapore was not to be just another weigh station on the trading routes of the British Empire, but rather something distinctly more – a free port protected by naval warships. Raffles himself fell to ill health and returned home to England to die in 1826. However, before leaving, never to return, he gave William Farquhar explicit instructions regarding the future of the port – that Farquhar should maintain free passage of all ships through the Strait of Singapore. Further, to support and enforce this order, a military and naval presence was to be established alongside the trading post. From that moment Singapore was to be both a free port and a key naval garrison. The combination of these two roles was to be decisive in the history of the port of Singapore.

Being a free port meant relaxed customs and excise conditions to attract trade; it meant a port not exclusively for the use of the East India Company and the British. Being a free port also meant, crucially, relatively few controls on transhipment. This was at the very heart of Raffles’ dream for the port, according to Professor Peter Borschberg, of the Department of History at the National University of Singapore. “Singapore was always conceived and designed as a free port, and it remained so through the nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries as well.” This was a masterstroke in the development of the port. Unlike the ports in British-controlled India or the newly created foreign-controlled Treaty Ports of China, Singapore was not a major source of commodities or manufactured goods to be shipped out to the wider world like a Shanghai or a Bombay; nor was it the gateway to a potentially giant market for western goods, such as Canton (Guangzhou) or Yokohama. Rather Singapore’s existence hinged on becoming the most important calling station between India and on to the Far East. For once the much overused saying, ‘geography is destiny’, was true.

Singapore’s geographical location at a crossroads of the East and West was to be, from its very origin, fundamental to its success as a trading port. As Peter Borschberg adds, “If you come from West Asia or the Bay of Bengal and you wanted to go to the Far East, and you’re doing this either in the age of sail or in the age of steam, there are really just two entry points – the Straits of Malacca or the Sunda Strait.” Today the Port of Singapore remains the world’s most crucial transhipment point – Raffles’ initial dream has long been realised. Georgraphy has been Singapore’s destiny.

The Port of Singapore’s early development occurred in tandem with other major revolutionary changes to global trade. The new harbour rapidly grew – the first drydock known as Number 1 Dock was completed in 1859; the second, Victoria Dock, in 1868 to be followed by the Albert Dock in 1879. In 1900 what had been known as the New Harbour was officially renamed Keppel Harbour – the man who had chased the pirates away over 50 years before visited to witness the renaming ceremony. Captain, now raised to Admiral, Henry Keppel was 92 years of age. At the same time as the facilities were constructed so other changes occurred – in the 1850s trade opened with the Kingdom of Siam; the Straits Settlements were formed in 1867 giving Singapore greater access to the hinterlands of Southeast Asia and, crucially greatly increasing the volume and speed of West-East trade via Singapore, the Suez Canal was opened in 1869.

The Port of Singapore was already one of the world’s busiest. Ships crowded the harbour, labourers unloaded cargoes on to tongkangs – light wooden cargo boats – which took the precious cargoes down the Singapore River to be stored in warehouses and go-downs. The city grew up around the port, thriving from it, profiting from it.

The Three Networks

Singapore’s rapid growth was based on the three main networks of trade that flowed through the waters just offshore of the settlement. The Chinese Network connected all of Southeast Asia to the teeming southern Chinese ports stretching from Hong Kong and Canton up through Fujian to Amoy (Xiamen), Ningpo (Ningbo) and Shanghai – everything from lacquer ware and opium; pig bristles and eggs flowed through this network. The Southeast Asian Network linked the myriad islands of the Indonesian archipelago with highly valuable spices at its heart. Lastly the Indo-European Network connected the Far East to the ports of the Indian Ocean littoral and on to Europe. These networks were of course complimentary. Spices flowed into Singapore from remote Indonesian islands for transhipment on to markets as far away as London and Amsterdam where they fetched extraordinarily high prices; Chinese manufactured goods (in those days including pig bristle toothbrushes, fine porcelain, ornate furniture) went out to the world and vice versa. East India tea clippers moored alongside Chinese junks. As steam superseded sail so the Port of Singapore became a major coaling station. Pirates remained a problem – in the Malacca Straits and elsewhere – and so British warships on patrol were also a regular sight.

Within a decade of its formation the Port of Singapore had become the dominant port of Southeast Asia. It’s success at the heart of the three networks crucial, but its historic creation as a free port essential, to its success. Its largest regional rival, Batavia (now Jakarta), under Dutch control, retained cumbersome and often expensive restrictions. Both the English country traders and the Chinese junk traders deserted Batavia for Singapore. Tanjung Pinang in the Riau Islands, previously the main port for the spice trade, lost its position to Singapore too. By the turn of the century Singapore was clearly the dominant regional port rivalled only by Bombay to the west and Shanghai to the east.

King Rubber and Lord Tin

Singapore had once been the sleepy tip of an often somnambulant peninsula. But in the 19th and early 20th centuries that changed and brought another bonus to the Port of Singapore. As the British developed Malaya so Singapore became the Straits Settlements’ primary port of export. Across the world the demand for manufactured goods drove demand for tin; the development of the bicycle, the automobile, modern shipping, all drove demand for rubber and Malaya was the major producer of King Rubber and Lord Tin. Fortunes were created and invested in developing an infrastructure of road and rail that ran the length of the Malay Peninsula. Their final stopping point? The Port of Singapore.

The construction of the Johor-Singapore Causeway began in 1919. It opened to cargo trains in September 1923 and to passenger trains a month later. Steam trains brought tin, petroleum and rubber to the port as well as passengers for the liners that docked on both the coastal ferry services and the routes west to Europe via Suez and to all points East – Hong Kong, Shanghai, Kobe, Yokohama, Honolulu, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Vancouver. If you wanted to get to New York then take your pick – west via Suez to Marseilles or Southampton and then across the Atlantic, or east to California and then either the long route by sea via the Panama Canal or cross country on the new transcontinental railroads. The Port of Singapore really did connect the world. But take a train south from as far away as Bangkok, Butterworth (change for Penang) or Kuala Lumpur and the southern terminus was the Keppel Road and, after 1932, the Tajong-Pagar Railway Station – in sight of the port – a wonderful art-deco station of white marble with statues representing agriculture, industry, commerce and transport. A few changes of train might be required, but steam trains now connected the Port of Singapore to as far away as Kunming and Chongqing in China; across the vast expanses of French-controlled Indo-China and even into the heart of Burma.

War and More War

The First World War was to have a profound affect on the Port of Singapore despite the conflict never directly reaching the country. The port’s economy boomed as Britain sourced unprecedented levels of crude rubber, oil and tin from the country to fuel the nation’s war machine. A new flag was also seen fluttering from ship’s masts in the port too – the Stars and Stripes. Between 1912 and 1914 only one major cargoship flying an American flag called at Singapore. In 1915 over seventeen large American-flagged cargo ships called at Singapore. In 1917 (when the United States entered the war in Europe) over twenty US-flagged ships called at the port and three companies – the newly formed Singapore-Pacific line, the Waterhouse Steamship Line of Seattle and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company of San Francisco – had commenced regular services between Singapore and the Pacific coast of the US. Even after the armistice, when the war ended in Europe, demand for oil, rubber, tin and a host of other commodities boosted the port’s revenues. As it celebrated the centenary of its founding by Raffles, back in 1819, Singapore’s port was at its zenith in terms of shipping tonnage, profits and cargo volumes. It seemed that both war and peace had been good for the Port of Singapore.

And the port’s strategic importance as a lifeline during the Great War did not pass unnoticed in London. Nor did the growing power of the Japanese Imperial Navy in the Pacific and China Seas. Cash-strapped as the British Empire was after the devastation of the war money was found to build a massive naval base in Singapore. Construction began in 1923 and was eventually completed in 1939 at the then phenomenal cost of $500m. Adjacent to the commercial port the naval base featured the world’s largest drydock, the third largest floating dock, enough fuel storage tanks to support the entire Royal Navy for six months and all protected by heavy 15-inch guns positioned in Fort Siloso, Fort Canning and at the new Royal Air Force base at Tengah. Upon completion Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, declared Singapore the “Gibraltar of the East.”

But it was not to be. Singapore was to be a naval base without a fleet. As the Second World War spread from Europe to Asia in 1942 after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, the European empires in Asia crumbled. The Japanese occupied French Indo-China, took the strategic port of Shanghai and then Hong Kong on Christmas Day 1941. Singapore was next in their sights. The Battle of Singapore raged from February 8 to 15, 1942 and ended in a British surrender. The Japanese Imperial Army occupied both the naval base and the commercial Port of Singapore. Now prime minister, Churchill called the fall of Singapore to the Japanese the “worst disaster” and the “largest capitulation” in British military history. The next three and a half years were to be dark ones across a Singapore under Japanese occupation. But in August 1945 Tokyo surrendered and Singapore, and its port, were liberated. The next phase of the port’s history was to be as part of a newly independent Singapore and to take place in a world which was to see, in technological terms, arguably even more change than the previous 100 years.

Paul French’s 10-page special on the history of maritime Singapore featuring fantastic archival images forms the centerpiece of the recently published Splash Market Report on Singapore, a 60-page magazine, readers can access online for free by clicking here.