Inside the collapse of common equity

Making his writing debut for Splash our New York correspondent Greg Miller gives his view on the year in ship finance. Greg, one of the best writers on ship finance, will be penning a monthly column from Wall Street to appear in a new sister title starting next month.

If common stock is the acid test of investor sentiment, then shipping just flunked the exam. It has been by far the worst year for common-equity sales since the industry’s broader move onto Wall Street in the early 2000s, and the reason behind the collapse does not bode well for 2019.

NYSE- and NASDAQ-listed commercial shipowners (excluding offshore and cruise) raised only $648m via follow-on offerings of common stock in 2018, and of that, $110m was bought by related parties. Two high-profile IPO attempts – by John Michael Radziwill’s GoodBulk and Angeliki Frangou’s Navios Containers – failed to price.

US-listed companies raised almost five times as much from common-equity sales last year ($3.1bn), and over seven times as much ($4.6bn) in the record year of 2014, according to statistics derived from securities filings. The previous nadir for US-listed shipping companies in the modern era was $1.4bn from common-equity sales in 2011, more than double this year’s tally.

Public owners reacted to the common-stock drought by selling other types of securities instead, namely debt securities (dollar-denominated secured and unsecured notes, convertible bonds, and kroner-denominated bonds) and perpetual preferred equity (PPE). Including all securities types, NSYE- and NASDAQ-listed owners garnered total gross proceeds of $4bn in 2018. That’s down 43% from 2017 and 51% from the all-time high in 2014, but it’s not the low point. It easily tops the $3bn levels grossed in both 2015 and 2016, and is well above the low of $2.6bn set in 2011.

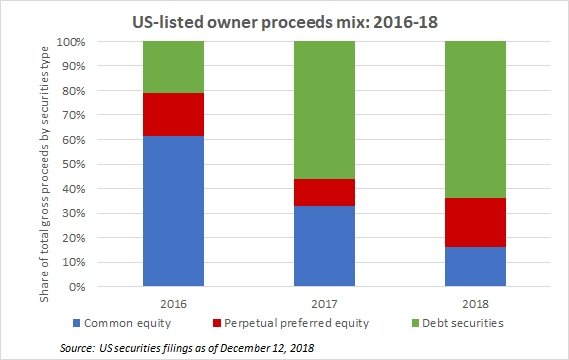

What’s particularly telling is how the mix of capital-market proceeds has changed (see chart). In 2016, common-stock sales accounted for almost two-thirds of total proceeds, with PPE and bonds combined at just over a third. This year, common-stock sales accounted for a mere 16%, with PPE at 20%, and debt securities at 64%.

Clearly, the goal of shipping investors has shifted. If you buy common equity, you share in the upside. You’re betting on the cycle and believe the next boom is just around the corner. In contrast, if you invest in bonds or PPE, you’re looking for fixed-income returns, generally in the 8-9% range: an interest payment in the case of bonds or a fixed dividend in the case of PPE. You don’t get the upside if the freight market spikes. You’re simply betting that the issuer will avert default.

The transformation of the type of securities being sold confirms that far fewer public-market investors believe timing the shipping cycle (‘buy low, sell high’) is a bet worth taking. They’re more informed, and there have been too many false starts over the past decade. Private equity agrees, increasingly shunning ship purchases and instead pitching owners on high-interest credit funds.

Today’s shipping investors increasingly prefer to make their money like a bank does, by renting out capital for a fee, not like a shipowner does, through asset appreciation and freight income. And the more this prejudice becomes entrenched, the harder it will be to resuscitate common-equity sales – an important source of shipping finance – in 2019 and beyond.