Is the dry bulk market set for a super-cycle?

In his regular monthly column, Pierre Aury discusses how a super-cycle could emerge.

During the Maritime CEO Forum held recently in Singapore the question was asked about a possible, or at least a plausible, new super-cycle looming in dry bulk. The moderator of the dry bulk market outlook panel noted that geopolitical risks tend to extend tonne-miles and with just 6.5% of fleet on order, and the fleet getting a lot older dry bulk was in a “honeymoon period” on the supply side.

One of the panellists commented that there was a case for an upcoming supply-driven super-cycle based on the assumptions that war in Ukraine will continue, and China is opening up.

But before we get any further what is a super-cycle? According to the Bank of Canada a super-cycle is simply an “extended period during which prices are well above or below their long-run trend.”

The bank describes the driving mechanism behind a super-cycle as “the interaction of large, unexpected demand shocks and slow-moving supply responses.”

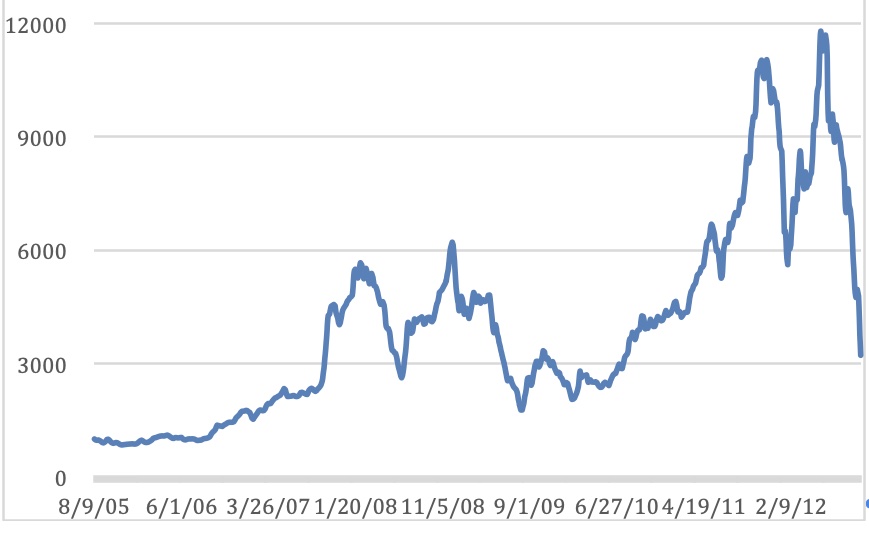

At the macro level, the bank has identified only four super-cycles since 1900. In dry bulk shipping since 1980 there has only been one driven by China becoming the workshop of the world. This super-cycle started in 2001 and ended in tears in the summer of 2008 as shown by the Baltic Dry Index (BDI) in the graph below.

China’s GDP was multiplied by 3.5 between 2001 and 2008 which led to a jump of 1,100% for the BDI over the same period.

Four macro super-cycles in 120 years and one dry bulk super-cycle in 40 years. The odds are clearly more in favour of a looming market spike rather than a super-cycle especially because China is facing the combination of a declining population together with post-covid reshoring policies enacted by numerous developed countries. As far as Ukraine is concerned and with no disrespect to its suffering population, with a pre-war GDP of $200bn or 0.2 % of world GDP it can hardly be seen as a potential driver behind a new super-cycle when the war is over and reconstruction starts. Regarding changes of patterns of trade generated by the war which are indeed real, they cannot be seen fuelling a super-cycle either as they are one-off events. So that’s it then, no case for a super-cycle around the corner in dry bulk then?

No, in fact, there is a case for a looming super-cycle. A super-cycle, which could make the previous one look like a spike or even a blip. Not a super-cycle driven by China or India or a war but a super-cycle driven by the entire world transitioning to a zero-carbon economy. In plain English this coming super-cycle, if it happens, could be driven by the fact that we will need to become much more carbon-intensive first before we become leaner and end up carbon-free. A case of making an alcoholic drink more alcohol in order to wean him off alcohol.

The world has embarked on a journey toward zero carbon emissions by 2050. In that short period of time, the world needs to build an entirely new carbon-free energy infrastructure. This will require a massive amount of raw materials – coal, oil and gas – as it will take years before wind turbines, solar panels and batteries are manufactured in plants only using clean energy. In dollar terms, the International Energy Agency (IEA) is estimating that $4trn will have to be spent annually on building this new energy infrastructure. Until 2050 this equates to a hefty total of $104trn which is equivalent to one year of world GDP. And the spending has started. According to the IEA, 2023 will see about $1.7trn spent on clean energy technologies. Certainly shy compared to the required $4trn but getting there.

So is a super-cycle around the corner? Perhaps not, as the path on which the world has embarked to decarbonise itself using mainly solar and wind power without first decreasing its energy needs is flawed. At least until we can store electricity on a massive scale, to the tune of days worth of world energy consumption in fact, and that is not going to happen in the near future.

Until electricity storage technologies can be deployed, the world must keep its existing carbon-intensive electricity generation capacity in working condition and in fact increase it as global electricity consumption is massively going up due to the present policies promoting the use of electric vehicles. But worse if and when electricity storage capacity matches world energy needs the very low load factor of renewable energy production means will kick in. The load factor of a power generation unit is the ratio between the power actually produced over a period of time and its production if it was generating power continuously during that same period of time. Solar panels don’t produce energy at night and when it’s cloudy. Taking into account nights, clouds and the power production bell curve a solar panel is at best at 12.5% load factor, in fact less because the angle at which the sun hits it is always wrong. This is to be compared to around 70% for an average coal-fired power plant and 80% for a nuclear power plant. Simply put, the peak capacity of solar panels must be at least eight times (100/12.5=8) the electricity needs they are servicing and this doesn’t account for extra production to be stored for when they don’t produce.

So the path on which our fearless leaders have set us to reach the legitimate goal of decarbonising the economy is flawed. However, they hate losing face so we can be assured that these misguided policies will last so there is a case for a super-cycle driven by these policies… unless of course the shipping industry front runs it.