McKinsey slams liners for destroying shareholder value, predicts more consolidation

The container shipping industry is expected to continue to struggle with overcapacity and an inability to deliver value to shareholders, a new report from consultants McKinsey warns. The report suggests plenty more consolidation is on the cards for the sector.

McKinsey estimates liner shipping has destroyed more than $100bn in shareholder value over the last 20 years. Its profitability was particularly poor between 2011 and 2016, when the industry average return on invested capital (ROIC) was consistently lower than the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

“Overcapacity is the key reason for the poor performance, and, unfortunately, it is here to stay. The current supply of container capacity afloat is about 20 percent greater than demand. We understand the challenge that lines faced over the past decade (2007 to 2016): as competitors ordered new, more efficient tonnage, there seemed to be no choice but to do the same or fall behind,” the report noted.

Slowing growth is exacerbating the situation, McKinsey said. First, the economic malaise in many countries has hurt consumer spending. Second, global GDP growth is forecast at only 2 to 3% for 2017 to 2019, versus the 4 to 5% of the boom years. Last, and even worse, the industry’s GDP multiplier, which increased as supply chains globalised, is falling. At its peak, container trade grew at two to three times GDP. Now, the multiplier is about one.

“Many industry watchers are predicting the end of the destructive freight rate environment. Unfortunately, we are not so optimistic,” McKinsey posited.

McKinsey’s projections of supply and demand show a continued large gap for several years, closing only early in the 2020s—even with conservative assumptions on new ordering.

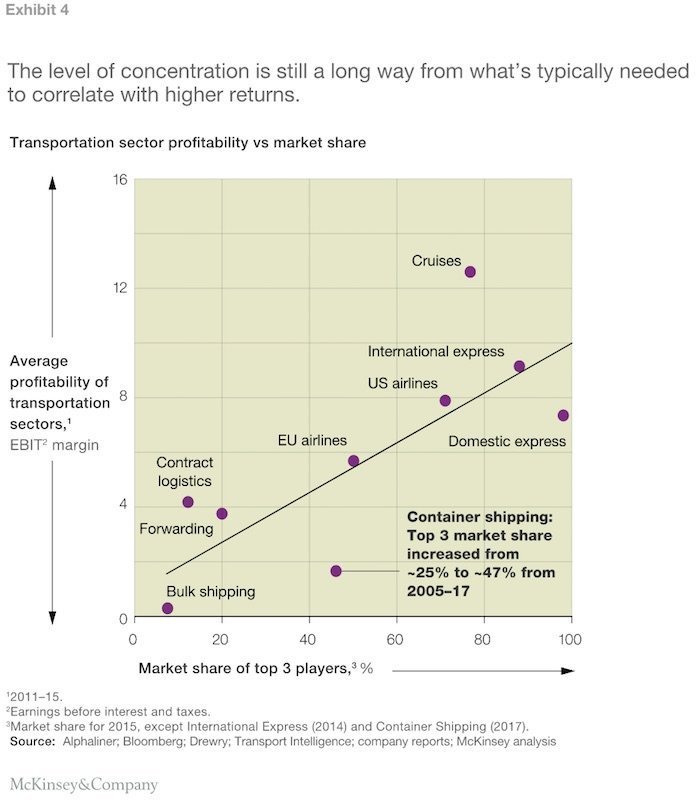

The industry is experiencing unprecedented consolidation as it responds to the negative environment but McKinsey reckons there is still plenty more mergers to come. The combined fleet capacity of the top five players almost doubled from 2000 to 2017, rising from 35% to 67%. Ten of the top 20 carriers in 2013 will soon no longer exist as stand-alone companies.

However, container shipping’s current industry concentration—where the top three players control 47% as of July 2017—is still below the level typically correlated with higher returns according to McKinsey.

Reference is made In the article to a reduction in the GDP multiplier. We believe simply using aggregate GDP as the driver to forecast port traffic is fundamentally flawed and even using a trend is over simplified. For example, UK GDP increased by 7.5% between 2007 and 2015 whereas the volume of cargo handled at UK ports decreased by 8.7%.

Ships carry physical goods, but in many advanced economies service industries dominate GDP growth and often only have a tenuous link to cargo volumes.

The impact of different sectors of an economy is critical, especially as they react differently to occasional major economic shocks. We adopt an unconventional principal component analysis to pick up this instability to portray many drivers of maritime cargo traffic.

To paraphrase JK Galbraith “Ideas that are commonly held, intellectually accessible, and yet fundamentally flawed, can be referred to as conventional wisdom”.

McKinsey manage not to mention the cause – the death of the conference system.