Does One Belt, One Road make commercial sense?

Following the recent summit held in Beijing in which the Belt Road Initiative (BRI) was the centrepiece, there has been much fanfare around the number of infrastructure MOUs being signed as well as speculation as to which countries / cities will benefit from the roll out of this grand plan.

In earlier articles I made reference to why Hong Kong was in a preferential position when compared to Singapore, and how Myanmar offers strategic leverage as China seeks a west coast marine / port. This solution is becoming increasingly important as initiatives with India / Pakistan run into geopolitical headwinds.

Whilst the public debate has been around the political and security concerns presented by such an ambitious plan, there has been an increasing number of debates around the commercial efficacy of the BRI, with many commentators suggesting that the BRI does not make commercial sense. It is also suggested that BRI is merely a crude attempt by China to reassign its oversupply of steel, concrete, rail capacity and expertise in building infrastructure.

Whilst there may be some element of wisdom in these suggestions, what is often missing in the analysis, is the underlying economic rationale to realign manufacturing and commercial enterprise from a coastal base to inland / western regions. This realignment is necessary as more efficient maritime routes were instrumental in motivating manufacturing centres to move from inland to coastal regions as shipping gave better access to markets. With this came distortions in socio-economic development. The BRI, by building important infrastructure, gives inland centres access to overseas markets and allows for manufacturers and allied commercial services to move into these areas.

However, this article will not go into the debate around the socio-political motivations around BRI, but will start the discussion around whether the BRI makes commercial sense. This is an important debate to have as we see recent declines in BRI spend and a slow uptake in using rail, suggesting that financial returns are now starting to take root. The commercial attractiveness can be usually compressed into the debate as to what is the cheapest form of transport logistics i.e. shipping versus rail.

When assessing the cost advantages of the different modal transport methods, it is evident that there is no quick and easy fix. The cost efficiency and effectiveness measures of a transport mode have multiple standards by which they can be compared. As found within the climate change debate, solutions given are based on biases driven by assumptions.

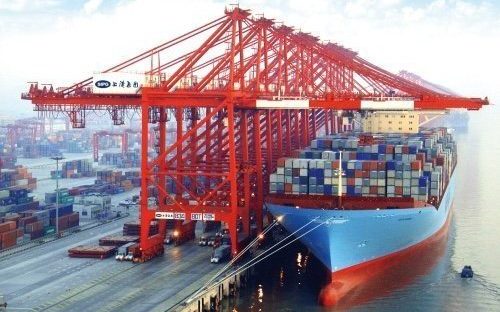

Many with shipping interests would argue that when using energy performance indicators, economies of scale in maritime are evident. A 2012 report from the USA Department of Transportation argues that shipping was the more efficient when looking at energy expended. By way of example, it is demonstrated that 1 ton of cargo using 1kwh of energy is demonstrated that it cargo can be transported 55 km, rail (electric) 20km, rail (diesel), 15 km. One must bear in mind that the largest of containervessels can carry up to 21,000 teu of cargo, with average cargo loadings of 10,000 teu. However, what the reports note is that this comparison is limited by limited port facilities, and no allowance for handling breakbulk. That is why we find it cheaper to ship containers across the Pacific Ocean to the east than to Africa across the Atlantic.

Research done by Richard Torian, also in 2012, and taking data from the US Department of Transport, shows that rail is the cheapest form of transport on a cost per ton per mile measure is used. Rail costs $0.03 and maritime is $0.1, road $0.37. A subsequent World Bank report also stated that rail was the most cost effective mode to transport cargoes. However, to apply this to the BRI is problematic as there is no uniform rail gauge from east to west out of China and rail is unable to run double carriage wagons. This goes to train length and time efficiency, particularly when one considers that 10,000 teu is equivalent to approximately 250 wagons.

At the moment the debate between which modes of transport are the most cost effective in the current BRI is hampered by the following:

- Rail gauge differences between countries,

- Poor infrastructure such as bridges,

- No single free economic zone across the region.

These would suggest that maritime trade is more cost effective and efficient today, therefore the BRI makes no sense. However, what must be accepted is that the BRI is a long-term approach, and takes a long-term view of commercial returns.

However, when looking at the significant changes taking place in modern supply chains, not only does it point to a significant changed paradigm, it also points to the strategic relevance of the BRI . These paradigm changes indicate that rail will become more cost effective as companies move towards:

- Need for fast and frequent delivery

- Smaller orders

- IT visibility across the supply chain requiring shorter notification times

- Improved cash holding by limiting the amount of cash held in L/Cs, etc.

Furthermore, it has been projected that by 2020 there will be more than 7.5m containers by rail from China to Europe. This would equate to roughly 750 vessels. According to Tony Restall, to transit the Suez Canal would cost these 750 vessels $600,000 each . This totals to $450m and will go a long way to fund a future BRI rail network. We already see the Chongquing – Xinjiang – Europe international railway currently move approximately 7,000 teu a quarter.

In summary, the BRI does make commercial sense when taking into consideration of the demands of modern supply chains. It makes more sense when seen through the prism of a new integrated logistics framework in which shipping / rail / road / air modes are rebalanced.

To ignore the socio-political aspects and focus purely on the commercial aspects, while making for a simpler article, is really a false dichotomy. The geopolitics are clear: China is being hemmed in by the US on the eastern seaboard and needs to find alternative trade routes. If such routes are not inherently commercially viable, then they have the economic clout to make them so.

We must be grateful that China is developing these new routes on a largely peaceable and constructive basis; a less benign, more militaristic regime could simply trample over Burma and open up their own west coast port, or roll through large tracts of Central Asia, as Russia has done in the past.

Your calculation that a 10,000 teu container ship corresponds to a 250 wagon train seems incorrect. A wagon is about two 20′ container lengths, no/yes, and so a double stacked wagon would then be 4 teus. Therefore should that figure not be a 2,500 wagon train, which would be around 20 miles long which seems unusually long? I am not an expert and so maybe I have gone astray somewhere in my arithmetic.

Although partially alluded to already by Richard C above, I guess in someways the secondary question is, does it matter if OBOR/BRI makes commercial sense?

10,000 TEU = 250 trains each carrying 40 TEU.

In Britain, with its particularly restrictive loading gauge, a the bed of a standard container wagon accommodates 3 TEU, so a rake of 15 wagons will carry 45 TEU, maximum.