Where’s the ceiling for box shipping?

Alan Murphy, CEO and founder of Danish container shipping consultancy Sea-Intelligence, ponders how close we are to topping out in terms of today’s record freight rates.

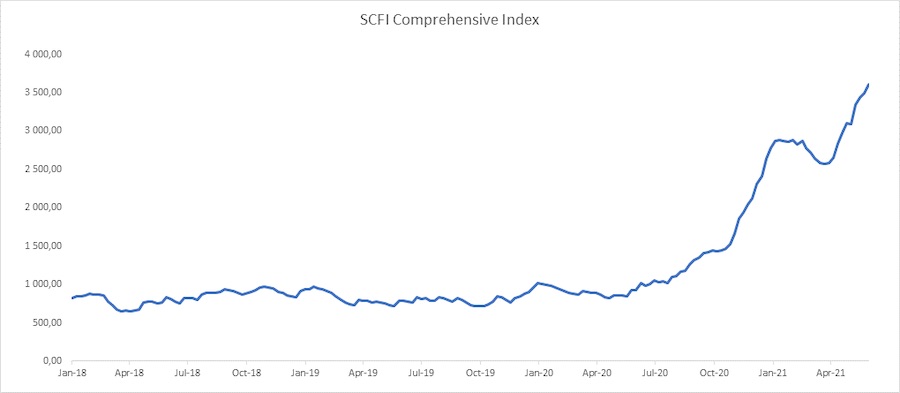

The Shanghai Containerised Freight Index (SCFI) hit new highs on Friday. For many months now people have been questioning how much higher spot rates can go. It’s a tricky one, as there are so many unknown variables in play.

First, the obvious one. We are now so far into uncharted black swan territory that no-one speaks from a position based on experience, data, or models, we’re all just throwing stuff at the wall and seeing if anything might stick. A year ago – or anytime in the past 60 years of container shipping – anyone suggesting spot rates of $20,000 per feu would have been laughed out of the industry.

Secondly, there’s not enough empty containers and slots, so it’s a game of musical chairs, where the music is money. Shippers with low-value-to-volume goods are being crowded out by three other types of shippers: A) High-value shippers that have greater margins to eat into, B) shippers with goods with little to no friction in passing on the costs up through the supply chain, and C) shippers who are able to enforce their contracted space and equipment guarantees, although I hear they are referred to as unicorns in this market.

Why are we the only industry that can only be profitable at full occupancy?

Another important stat to keep an eye on is the ratio of goods ready to ship versus placing new orders. If you have $500,000 in a box, but it is worth nothing in a yard in China and rapidly decreasing in value (fashion apparel, high-tech, seasonal products, automotive parts, perishables, pharmaceuticals, etc) you are willing to begrudgingly pay an awful lot of money to ship, if the alternative is spoilage or other type of massive value loss. On the other hand, if you are considering placing an order for 20 boxes of $500,000 of perishable goods, you will very likely consider whether you can postpone such an order, to a time of more reasonable freight. What is this ratio, no-one knows.

There’s not enough empty containers and slots, so it’s a game of musical chairs, where the music is money

The contract versus spot ratio of course also plays a role. As do the limited substitution options in air, rail, or near-sourcing. As does the contagion of equipment shortages across trades: Asia-Europe is experiencing quite anaemic demand growth, but rates are through the roof because there’s no boxes to move the cargo that has to move, due to the transpacific soaking up all the empty boxes. All trades are up from last year, but the SCFI is a weighted average of nine different trades, and many trades are far from as high as Asia-Europe and transpacific, and in theory they can go much higher, but how high and what’s the ratio? These ratios are all unknown generally, and even more so in terms of how the ratios are split across different value classes of container shipments.

High freight rates are driven by equipment and space shortages, which in turn are driven by a confluence of unprecedented US demand (due to pandemic shifts from services to goods) and supply-side disruptions: Port congestion, Covid infections and quarantines in ports (e.g. Yantian) and terminals, vessels being grounded due to quarantines, and the challenges of vessels getting stuck in canals, dropping boxes, or catching on fire. In the past 10 years, vessel incidents would be terrible for those immediately impacted, but they would not have any systemic impact, as the unaffected boxes and boxes waiting to be loaded would just go on the next half-empty ship, but all of the ships are full now. Meanwhile, European consumers have not increased their spending on goods during the pandemic, but are rather holding back until lockdowns are lifted, so once the US consumers can shift their consumption back to services, the Europeans might take over. On top of that, there have been massive drawdowns of inventories worldwide which will need to be replenished, and with US consumer demand for same-day and next-day shipping, we will need bigger inventories than in the past. Oh, and the traditional peak season is starting now.

When demand is strong and rate levels are as crazy as they are now, vessels don’t need to be full to be profitable. In the current stressed environment, I would wager that few shipping lines would be foolish enough to forgo cargo they have space for, in an attempt to keep rates high, but once this dies down a little, shipping line executives will start to seriously question why we’re the only industry that can only be profitable at full occupancy. The core product being sold – time-perishable capacity, i.e. you can’t sell the space after the vessel has sailed – is not unique to container shipping, we share that with not just all other freight modes, but with airlines, hotels, taxis, restaurants, cinemas, grocery stores, newspaper advertising, etc, and an endless stream of liberal professions that sell their time. All of these industries start to be profitable at 30-70% utilisation, but we can only be profitable at 90+% utilisation? Why is that?

When will all of this end? Only a fool would guess, so being a fool, I’ll say it is unlikely to end during this year, and likely to run well into next year.

Can rates go further up in the coming weeks? Certainly! Can they go down a little? Also possible! Will they go to $30,000 per feu? Not impossible. Will they go down to half of where they are now, in the near future? Unlikely. Will they ever go back down to long-term averages again? Very unlikely, carriers should have learnt their lesson. Will we ever see a return to 2015-16’s Asia-Europe spot rates of $200 to $300 per teu? No, but if we ever do, both I and the liner execs causing it, should find another industry to ruin.

Thanks for the insight of current box freight market to an common reader.

All this carrier will taste their own bullet after 2023-2024 when the most country return back as normal with the increasing numbers of vaccinated individuals. Clearly the situation nowadays not due to shortage of the equipment, but rather the slow rotations of the equipment itself.

Year 2020 saw CIMC had manage to produce 1 million teu’s of newly built of containers, which is insane. So, once the situation getting better, there will be a surplus in containers and those containers purchase in this period will put pressure to liner to sold off their old equipment which will be less than 10 years into sub sale market.

I believe, the carriers will make the most of revenue in this period in order to cover up their situation in the next few years ahead.