Maritime logistics unplugged

Ana Casaca, the CEO of World of Shipping Portugal, gives readers a detailed look at how shipping companies are embracing logistics in their own individual ways.

Maritime logistic is emerging as a new area of study. Worldwide, universities are drawing attention to it as an independent subject to be taught and not inside other subjects, as might be the case, even though a few universities have considered it in their curricula. The reasons leading to this wake-up call could be many, but the consequences of three events that the world has witnessed since January 2020 has spurred interest. These include the covid pandemic, the 2021 Ever Given containership grounding in the Suez Canal, and the Russia-Ukraine war.

Throughout this succession of events, the term maritime logistics came to the forefront. Never before has it been given so much attention, with the different media outlets and analysts drawing attention to the secondary effects caused by each event. The words were often used and very much linked to the bottlenecks witnessed in the ports of China due to the zero-covid policy as well as the prolonged port congestion occurring across the US west coast ports. Simultaneously, it was impressive to see how bottlenecks in some parts of the world constrained the remaining worldwide logistics and supply chain activities, having a strong multiplier effect, forcing ocean carriers to redesign some of their logistics operations and employ sweeper vessels to relocate empty containers.

As the situation became critical, some ocean carriers suggested that supply chain members shifted from just-in-time to just-in-case strategies. Such a shift would foster the building of inventories to minimise the impact that the existing bottlenecks were causing on the manufacturing industry and intermediaries (i.e., wholesalers, retailers, and other specialised intermediaries besides ocean carriers) to meet a sudden market demand derived from e-commerce activities and over which they had no control. In addition, as part of the middle mile, ocean carriers needed both the first and the last miles streamlined to increase their service reliability and overall service performance.

The situation also raised several shippers’ and receivers’ complaints in the US, contributing to a legislative change. The bipartisan Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2022 was enacted to level the playing field for American exporters and importers and give the Federal Maritime Commission tools to better control international ocean carriers and repress rising shipping fees being faced by consumers. Whether this was positive or negative is out of scope here; what is important to refer to is that events lead to changes, some good and others not so good.

Therefore, much has been written and discussed about logistics and supply chain management. The outcome of many of these writings and discussions targeted finding solutions to a myriad of problems to make logistics and supply chains more streamlined and resilient to different unexpected shocks. They highlighted how transport infrastructure and adequate transport policies are relevant to streamline the flow of goods to avoid congestion at critical nodes, some of them international gateways to international trade, and how important it was for the different economic players to adopt new logistics strategies.

With this background, maritime logistics was very much linked to one market segment, container shipping, given the nature of the cargoes being carried inside the containers and their ability to move between modes. However, such an approach limits its concept. First, the shipping industry embraces many shipping segments other than container shipping. Secondly, the current approach limits itself to the port logistics concept and port-hinterland connectivity issues.

Logistics, supply chains and strategic logistics

Explaining the difference between logistics and supply chain is always challenging, mainly if one is in front of a classroom listening to the concepts for the first time, thus requiring some creative approach to clarify both concepts. A straightforward approach to overcome this situation is to highlight that logistics, independently of the definition chosen, such as the one provided by the Council of Logistics Management (now the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals) in 2000, that defined logistics as “that part of the supply chain process that plans, implements and controls the efficient flow and storage of goods and related information from the point of origin to the point of consumption in order to meet customers requirements”, results in a system, namely a logistics system, in which numerous activities are performed (production) to meet customers’ requirements (output) from its resources (inputs) within the shortest lead time, supported by two flows (i.e., the information flow and the added-value flow) running in opposite directions.

Such a definition and approach show that logistics goes beyond a simple physical distribution operation, even though the concepts have been used interchangeably. Instead, it is a strategic process that adds value, allows product differentiation, creates comparative advantage, and renders profits to the organisation. As part of this strategic process, activities such as order processing, inventory management, procurement, planning, production, transport, warehousing, materials handling, and packaging take place; while common to all logistics systems, the approach to their fulfilment depends very much on the type of product considered.

While such an approach is a simple one that can be justified when dealing with local markets, where suppliers are close to production and production is close to consumption, the situation becomes more complicated when considering global markets as the ones currently in place. In order to accommodate this transformation, different logistics systems must be brought together, each of them performing its role, from supplying raw materials, parts, components, and modules to manufacturing the products that the different consumption markets eagerly await to distributing them in the most diverse points of the globe, thus originating supply chains, whose complexity depends on how far these systems are from each other and on companies’ corporate/business strategies.

Trade liberalisation, improved technologies and communication systems, improved logistics connectivity and lower transport costs have contributed to this situation. However, the presence of complex supply chains, where their members are in different parts of the world, must be fully articulated since all parties participating in it, namely suppliers, manufacturers, intermediaries, and end-users, either business customers or individual consumers, must fulfil their role within determined time frames to avoid delays, fluctuations in demand that tend to be progressively larger upstream, and market losses. Therefore, the successful design of supply chains to produce any product, be it goods or services, results from comprehensive strategic procurement approaches that will, eventually, define the location of facilities (nodes) through which products in different stages of production are conveyed (arcs), and how these are conveyed, i.e., by which modes or combination of modes.

In defining logistics strategies and integrating them, a strategic logistic approach emerges as the sum of innovative strategic actions, which is only possible to develop in the presence of solid logistics competencies. Such an approach is very positive since it renders dynamism to the supply chain system, helps companies undergo their business process reengineering and organisational changes, contributes to companies redefining their corporate strategies and obtaining sound synergies, and above all, puts in place the strategies defined to meet corporate/business goals and objectives.

As part of this process, the role of intermediaries along supply chains has evolved throughout the years to accelerate the distribution of supplies and finished products to different markets. So long are the days when manufacturers were involved in distributing their products (1PLs). Instead, the market promoted the emergence of 2PLs and 3PLs, which became further integrated (4PLs and 5PLs) as their control over manufacturers’ activities increased to increase their power along the different chains in which they participate.

Such integration, while resulting in a greater responsibility over supply chain activities, also contributes to obtaining a higher bargaining power, for instance, with ocean carriers when negotiating their contracts of carriage of goods, particularly in market conditions in which overcapacity dominates, and there are no bottlenecks to absorb capacity as witnessed during the covid pandemic. This intermediary’s negotiating power is well demonstrated by the different shipping indexes, particularly those related to container shipping, and confirmed by Emily Stausbøll, market analyst at Xeneta, when claiming that shipping companies struggled to get freight rates up above their break-even levels during the decades pre-covid.

Shipping and the service supply chain

For many years, the shipping industry has lived in a world of its own. Being the oldest mode of transport with about 5,000 years of history, as claimed by Martin Stopford, may justify this situation. However, a more plausible reason may be that shipping requires a unique business approach, given its international character and the need for a regulatory framework applicable worldwide to establish a level operating playing field. For these reasons, many textbooks have characterised maritime transport as a highly capital-intensive and risky industry, the backbone of international trade and the global economy, responsible for more than 80% of the volume of goods traded internationally, with this percentage being even higher for most developing countries.

From this traditional approach, in which shipping moves cargoes on a port-to-port basis, the industry serves the suppliers, the production/manufacturing and the consumer markets, carrying a wide variety of goods (i.e., raw materials, semi-processed goods and finished goods), in different physical states either in bulk or packed forms along different tradelanes. However, given that shipping, like the airline industry, is truly international in the current global economic context, this traditional approach, although valid, is not sufficient; therefore, shipping must be addressed from a logistics perspective.

From a logistics perspective, maritime transport performs two functions: the first one is the movement of goods from loading port A to discharging port B, and the second one is the temporary storage of goods between these ports. Considering that storage activities add no value but cost to the supply chain, whether goods are in a port or a warehouse, this temporary storage provided by transport grants receivers of goods the possibility to determine the loading and/or discharging ports for their cargo to attain better management of their inventory levels along their logistics pipeline and the ability to work on a just-in-time basis.

Moreover, from a logistics perspective, shipping is now part of integrated transport systems which support supply chains and networks of supply chains. While the globalisation of the economy has fostered this integration, acknowledging the impacts transport has on the environment further accelerated it. From a port-to-port service delivery, shipping is now an element of transport chains that provides door-to-door services. However, this modal integration does not become straightforward because the different transport modes have different transport capacities, requiring the presence of buffers along the transport chain traditionally performed by ports, dry ports, freight villages and yards to accommodate these differences.

Against this logistics perspective of the shipping industry, it is necessary to dig further upstream and see shipping from a marketing perspective, given that logistics is the practical side of supply and distribution channels, both under the place dimension of the marketing mix. Moreover, unlike manufacturing goods, the shipping industry, like any other transport industry, delivers services, which are intangible products and depending on the shipping market in which it operates, the level of service intangibility varies. For example, according to the goods services continuum, service intangibility in shipping can be higher in the tramp market and not so high in container shipping, given the tangible elements associated with the service.

The issue gets more complicated when shipping companies are required to identify the business or businesses in which they participate. As suggested by Stephen Shaw when analysing the airline industry, the most obvious answer would be to define their business participation in terms of what they, i.e., shipping companies, do, and for that, it would be pretty easy to say that they are industry players. However, such an approach needs to be sufficiently detailed since it does not consider shipping companies customers’ needs and how they can satisfy them to avoid competition.

Again, according to Stephen Shaw, possible business areas are transport, leisure, logistics and selling services, and given the current composition of the fleet, the numerous shipping companies will be working in at least one of these areas. The different strategies implemented by the two leading container shipping companies MSC (not including MSC Crociere) and Maersk, highlight that. Maersk focuses on performing ocean transport services and delivering logistics services to become a global logistics integrator, which aligns with its overall strategy, the acquisitions carried out during the pandemic and the current strategy of consolidating its brands after announcing the break-up of the 2M vessel-sharing alliance with MSC in two years.

Conversely, according to Alan Murphy, Sea-Intelligence CEO, MSC appears to be more interested in ocean transport services, even though its website draws attention to inland and air cargo solutions and claims that the company is focused on intermodal transport, expecting to make significant investments in this area. Suppose MSC is focused on becoming a global logistics integrator. In that case, the focus on mass customisation that allows for service differentiation rather than mass production needs to be clarified, as in Maersk’s case.

These issues are important because maritime transport delivers services and is part of service supply chains, more precisely product service supply chains, that are demand-driven because the services rendered are pulled based on demand. Such features make the management of service supply chains more complex than the goods supply chains since human involvement and interaction are higher in service creation and delivery, and the possibility of storing services to be delivered later is nonexistent.

Shipping and Porter’s value chain model

In order to have a better view of how the product service supply chain fits within the shipping industry, one needs to use Porter’s value chain model; Porter’s value chain model is a framework that maps out how a business creates market value by identifying its primary and supporting activities. However, Porter’s value chain model presents a flaw. The model was initially designed for tangible products, not intangible ones, meaning that before the tangible product is bought, customers and consumers can try it and decide. With services, the situation differs. First, we buy the service, and only then do we use it, as it happens when we buy an air flight ticket, even though there are occasions when the service is produced and consumed almost simultaneously; this is the case with restaurants.

Shipping services, like airline services, follow the same principle. Shippers looking for the capacity to ship their goods buy the service first, to benefit from it at a later stage, sometimes without knowing the actual performance of the shipping company, mainly if they are newcomers, making their decision on which shipping company to use based on word-of-mouth or referral opinions.

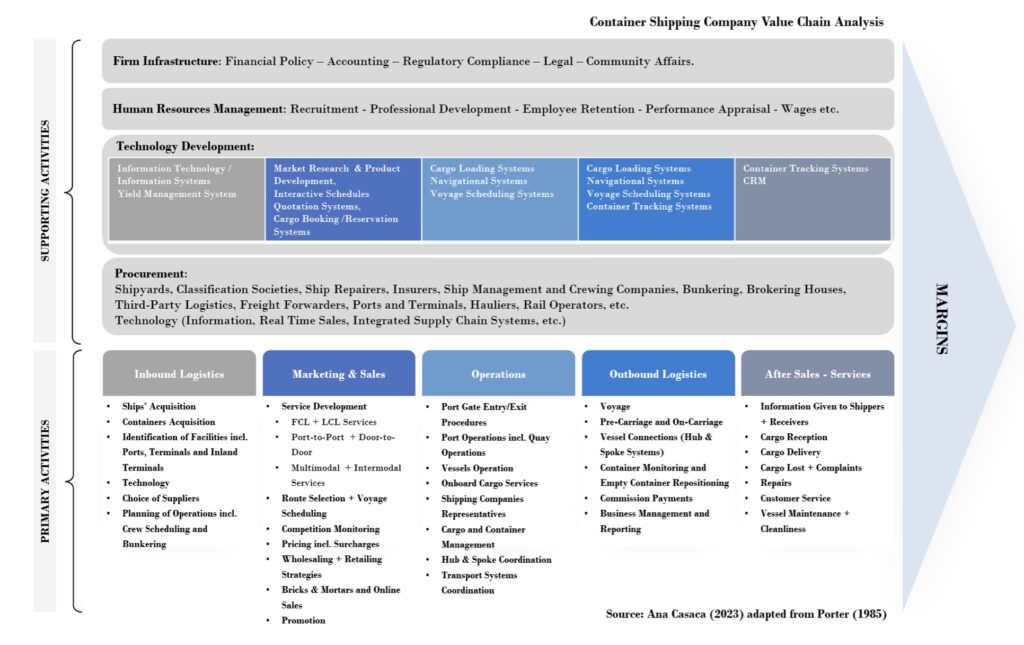

For these reasons, Porter’s value chain model needs to be adapted to represent the sequence of activities that shipping companies deliver, either port-to-port or door-to-door. Therefore, instead of following the traditional approach in which ‘Marketing & Sales’ activities occur after ‘Outbound Logistics’, the adapted model considers ‘Marketing & Sales’ after having defined its ‘Inbound Logistics’ and before ‘Operations’ having taken place (see Figure on ‘Container Shipping Company Value Chain Analysis’).

Still, the model in the Figure cannot be applied directly to all shipping markets because of their inherent structure. Having as an example the two opposite ways of ship operation, namely tramp and liner shipping, several activities identified in the figure for container shipping would be performed less intensely in tramp shipping. This is the case with the ‘Marketing and Sales’ activity. The distribution channels for service delivery used by tramp shipping companies differ from the liner shipping ones simply because tramp shipping companies do not require the heavy shore structure that liner shipping does. Moreover, in the tramp shipping market, the marketing relationship is one-to-one despite the contractual changes that can be made on charter parties. In contrast, in liner shipping, the marketing relationship is one-to-many, with numerous contractual arrangements and shipping companies having to decide whether to adopt wholesale or retailing selling strategies.

The figure also indicates that independently of the market segment in which ships operate, supporting activities are common to all. However, there might be slight differences in what concerns ‘Technology Development’. For example, tramp shipping operations do not require interactive scheduling systems, quotation systems or even cargo booking /reservation systems and container tracking systems due to their inherent activity, even though others, such as navigational systems and cargo loading systems, will continue to be critical to guarantee ships navigability, manoeuvrability, buoyancy, stability, and seaworthiness. Therefore, when combining the definition provided by the Council of Logistics Management in 2000 and the figure on container shipping company value chain analysis, it is clear that maritime logistics is much broader in scope.

Maritime logistics defined

Maritime logistics as a concept involves several logistics systems. Besides the shipping company logistics system, which is the core of the overall activity, the other logistics systems include suppliers’ and distributors’. So, when dealing with a port/terminal logistics system, only one logistic system of one supplier is considered. Given that a tradelane serves different ports in container shipping, shipping companies may be confronted with different port logistics systems due to the specificity of their operating processes. One strategy to avoid the disparity of different port logistics systems is to outsource the same port operator, which may explain why some mega carriers have also invested in this business activity (MSC – Terminal Investment Limited Sàrl¸ Maersk – APM Terminals; CMA-CGM – Terminal Link and CMA Terminal; Cosco Shipping – COSCO Shipping Ports Limited).

Therefore, the number of outsourcing activities varies depending on shipping companies’ capital outlay and their capacity to insource. While it is acknowledged that shipbuilding and demolition activities will be outsourced, outsourcing shipmanagement and crewing is not straightforward, even though it has become a best practice over the years. Important to say that activities prone to outsourcing are many; it will depend on the companies’ corporate/business strategies and the extent to which they want to control the upstream supply chain.

A similar situation occurs at a distribution level. The level of disintermediation attained by shipping companies determines their dependence on intermediaries and their bargaining power. While this bargaining power is settled in tramp shipping through the established commissions, the situation differs in the liner market with higher dependence on intermediaries. Acknowledging that container shipping relationships are one-to-many, the presence of intermediaries allows companies to concentrate on their core activities. However, they act as gatekeepers preventing shipping companies from accessing relevant market information, in this case, on the customers’ actual needs.

Therefore, the level of disintermediation defined by shipping companies depends on market conditions and volumes of cargo handled. In markets where cargo volumes are considerable, it may be feasible to disintermediate fully, while in others, it may be worth working with intermediaries. Any decision will have to be made on a case-by-case basis. In the end, a mixed strategy is attained, which proves to be positive. While allowing shipping companies to have accurate information and data on the distribution production costs, it also allows them to benchmark their distribution services against the distribution services provided by other intermediaries and vice versa to improve the quality of the service rendered.

In light of this, voyage planning becomes critical in shipping companies’ product-service supply chains. With a focus on cost minimisation, profit maximisation and carbon footprint reduction, voyage planning will finetune both procurement and distribution activities. In addition, it will determine where ships will bunker, get their water supply, change crews, get their stores and spare parts, and even drydock the vessel for periodic repair and maintenance for certificate renewal. Moreover, port and terminal choice and voyage optimisation must be considered as part of voyage planning. On the one hand, port and terminal choice will determine the possibility of ocean shipping integration in the most diverse transport systems; on the other hand, voyage optimisation will reduce the time at sea and port while contributing to increasing the number of voyages performed by ships annually, thus contributing to improved productivity at sea.

This highlights how vital voyage planning is for procurement, buying and purchasing activities and vice-versa. Therefore, the research studies being carried out on port / terminal choice belong to a tiny research area within the broad scope of shipping companies’ procurement activities. Furthermore, in some studies concerning voyage planning and optimisation, a variable addressing procurement could be incorporated to reflect market constraints, eventually leading to changes in the outcome.

Furthermore, in the particular case of container shipping and in tramp shipping when in the presence of contracts of affreightment, which requires high service levels, voyage planning also provides information on the capacity needed and eventually determines the extent of cooperation that companies must engage to guarantee an available capacity on a regular and frequent basis, depending on the trade being served. This explains why tramp shipping has been witnessing the establishment of joint ventures in the form of shipping pools and container shipping has been witnessing the establishment of cooperative agreements in the form of ‘slot sharing agreements’, ‘slot charter agreements’, ‘vessel-sharing agreement’, and ‘shipping alliances’.

From a logistics perspective, these cooperative agreements are how shipping companies manage their inventory, which is often translated into deadweight tons and transport equivalent units depending on the shipping segment. Therefore shipping companies’ inventory management concerns not only the materials and spare parts needed to operate their ships but also the management of the available capacity. For this reason, time charter parties are often negotiated with additional periods of three, six or 12 months to allow charterers better management of their capacity to suit market demand levels. Procuring a ship to replace another ending her contractual arrangement is a laborious, time-consuming and expensive task, particularly if it includes travelling.

The range of logistics activities identified before will have different levels of importance. Out of them, two will be significant to a shipping company’s success. Procurement activities will play a significant role mainly when shipping companies are being established, given that decisions must be made at all levels. Some procurement decisions will be considered strategic, like the choice of ships, the shipyards where they will be built, crewing and ship management, bunkering and ports/terminals requiring a detailed market analysis. Others will be less strategic, such as ship-chandling decisions, which are easier to replace and not considered fundamental as they are not prone to the international regulatory framework that governs the industry.

As shipping companies grow (or retrench), inventory management will replace procurement in terms of importance. Inventory management becomes critical since there will be moments when shipping companies need to add capacity (for example, charter-in, buying in the second-hand market or ordering new ships) or let go of capacity (for example, charter-out, selling in the second-hand market or demolishing) to maintain the business viability. The most critical issue is to understand that once the company is running, there are essential logistics systems that companies must learn about for each ship lifecycle, which will be added temporarily to their structure, as is the case of shipyard logistics systems when ordering new ships which directly impacts on companies human resources management.

Overall, maritime logistics is much broader in scope than initially presented. It must be seen as the sum of all logistics systems of shipping companies’ product-service supply chains, where each of them plans, implements and controls their flows for the efficient performance of the industry as a whole. Moreover, it allows all business players of shipping companies’ product-service supply chains to see their business more systematically, contributing to continuous process improvement. Furthermore, it opens the scope for developing new research areas worth investigating and optimising, for instance, sale and purchase logistics, shipyard logistics and bunkering logistics, thus contributing to the overall maritime industry performance. Inspired by Captain James Tiberius Kirk of the Starship USS Enterprise, maritime logistics allows shipping business players “to boldly go where [they] have never gone before.”