Nasty, brutish, but short; shipping must navigate gaping downside risks to avoid a great depression

A rapid market recovery is dependent on the success of policy responses and failure could be disaster, writes James Frew from Maritime Strategies International.

To state the obvious, the likely impact of the COVID-19 epidemic is without precedent within shipping and without recent parallel in terms of its more human impacts. However, from a shipping industry perspective, parallels with the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) post-2008 are instructive in understanding the likely dynamics of the recovery. In short, this time round the recession will be far more acute, but has the potential for faster economic recovery, whilst limited oversupply in both the shipping and shipbuilding markets facilitating a faster rebound should the global economy pull out of its nosedive.

Macro-economically, this represents an unprecedented shock. In contrast to either the Great Recession or Great Depression, the economic downturn did not start endogenously from a financial bubble, but instead represents an exogenous shock. Whilst there is certainly a real risk of the situation evolving into a full-blown financial crisis, there remains the possibility that this can be avoided. The importance of avoiding a financial crisis is based on the well-established body of literature discussing how financial crises lead to longer-term downgrades to economic output (indeed, Ben Bernanke’s doctoral thesis was on the topic).

Unsurprisingly, there is little corresponding literature on the dynamics of economic recoveries from viral pandemics, but we would suggest that a few themes are key to determining the recovery trajectory – the length of time social distancing continues, the spill-over effects into the financial sector, the likelihood that some people who have lost their jobs will remain out of work for a prolonged period and lastly – and most importantly – the policymaker response.

Towards a V-shaped recovery

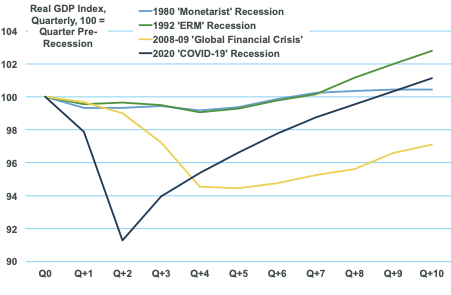

It is beyond MSI’s remit to meaningfully comment on each of these specific variables, but instead we can draw some general comparisons with historical downturns. We plot the recovery trajectory of European economies following three recent historical recessions. As it shows, the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) recession – which in some ways as an external shock to an otherwise relatively benign economic environment – saw growth struggle for a year before returning. The 1980s Monetarist recession took longer to unfold, and saw slower growth as economies continued to contend with ongoing tight monetary policy designed to tackle inflation.

The Global Financial Crisis was the most profound recession in terms of its severity and the time required to make up lost ground, with output remaining below the previous trend for years. At present, MSI’s Base Case – shown in the Chart below – is predicated on the assumption that the COVID-19 induced recession will follow a ‘V’ shape, with a staggeringly acute decline induced by social distancing reversed as the economy restarts, aided by full-throated government stimulus.

Chart – EU 27 + UK economic trajectories

There is no question that this relatively benign view of the medium-term is subject to gaping downside risks, which are so numerous that it is hard to know where to begin. Perhaps the most obvious is that efforts to restart economies lead to a resurgence in the virus, and as a result the downturn in economic activity is far longer. This scenario both damages the economy directly and makes a longer-term loss of productivity through unemployment, capital destruction and financial contagion far more likely. In the most extreme scenario, if policies to restart economic activity fail, the unwinding of existing economic relationships will bear a greater resemblance to the 1930s than the 2000s.

China’s changing demand mix

Whilst governments are unrolling policy responses, which in the UK and US have been unprecedented in size and scale, in reality there are no political precedents for such a pandemic, and there is likely to be some delay or inefficiency in the translation of any such stimulus into the real economy, and potentially even further delay in the resulting pick-up in economic activity driving increased shipping demand.

This fear is compounded by the situation in China. Whilst MSI still believes that China is likely to take advantage of low commodity prices by boosting imports and stockpiles (as it did in 2009 and 2015), the longer-term effects of Chinese stimulus may well be less leveraged towards supporting raw material imports than they were previously. This is both a function of fiscal limits – particularly relating to concerns around local government debt – but also a question of how much additional infrastructure China actually needs given the scale of previous infrastructure splurges.

In other words, the longer-term macroeconomic impact is cloudy, but will doubtless be sizeable in the short-term. Where we do have significantly more visibility is the state of the shipping markets.

In stark contrast to the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (or indeed the 1980s recession), orderbooks and more broadly shipbuilding capacity look far more under control. The dry bulk orderbook stood at a whopping 72% of the fleet in 2008; by contrast today the orderbook is less than 5% of the fleet. Tankers are also more restrained, with a fleet to orderbook ratio today of around 9%, relative to 43% in 2008.

Shipyard capacity under control

Structurally, we also believe that shipping is better positioned for a rapid recovery thanks to the lack of shipbuilding overcapacity that blighted the 2010s. Since 2011 – marking the high-water mark for shipbuilding capacity as yards completed their pre-GFC expansions – the shipbuilding industry has shed 33% of its capacity and currently has a forward orderbook spanning around 2.3 years.

Whilst some further consolidation is likely, with all three shipbuilding nations still in the throes of mergers which potentially could lead to just four major shipbuilders globally (Samsung, DSME/Hyundai, JMU/Imabari and one Chinese state-backed builder), much of the consolidation has already taken place. This is critical, as yard overcapacity both shortens orderbook lead-times – quashing recoveries before they start – and also applies downwards pressure to newbuilding prices.

The latter point is particularly relevant in the context of investments in assets. Because newbuilding prices provide the upper reference point for resale values, falling newbuilding prices typically imply a more general deflationary environment within shipping, which in turn undermines the potential for profitable asset-play.

COVID-19 represents an unprecedented challenge for shipping. This article has not touched on the very real human suffering, either globally or for seafarers, port workers and other players in the industry, nor the almighty logistical nightmare which the liner companies in particular are trying to unpick. However, from a supply/demand point of view we can draw some parallels, and they are more hopeful.

Whilst of course the length and severity of the epidemic are presently unknowable, our Base Case is that the recession will be unprecedented in ferocity but also short and sharp. Coupled with a far more supportive supply side for most sectors (with LNG and Cruise arguably exceptions), there is certainly the potential for shipping to recover sharply over the course of 2021. However, there is no doubt that risks remain, and if the policy responses are bungled or the epidemic continues unabated, then the Great Depression, rather than the Great Recession, is a better parallel.

The shipping industry is a crucial asset that governs a nation’s economy.Potential importers as well as exporters are suffering with an economical low ….

But i guess its just a temporary phase and again shipping will be back in the form very soon.

Thanks for sharing your thought.