What’s killing our seafarers?

It is easy to forget the strength and brute force that the ocean can render. Few appreciate this more than the seafarers that ply the world’s waterways in support of global trade and economic growth. Ships are not designed for the calm waters of a protected harbour.

As a community, we have recognised the need to improve the safety of life at sea. Our present collective international efforts started in earnest in 1948 when the SOLAS Convention was first adopted at the International Maritime Organization’s predecessor, the International Maritime Consultative Organisation (IMCO). Where early SOLAS requirements focused on materiel standards, more recent updates include operational issues through the International Safety Management Code; crew training and competency issues through the Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers Convention and most recently, the safety and welfare through the International Labour Organisation’s Maritime Labour Convention.

But we should ask ourselves, have we gone far enough —do we go far enough— to look after the safety of those that ensure the reliable and efficient delivery of raw materials, commodities and finished goods? At the Liberian Registry, we hold a weekly management meeting and a standing item on the agenda is a summary report on seafarer casualties. Unfortunately, this is a weekly reminder of the inherent dangers and the difficulty of working in remote areas of the world. Rarely a week goes by where we are not required to investigate the death of a seafarer.

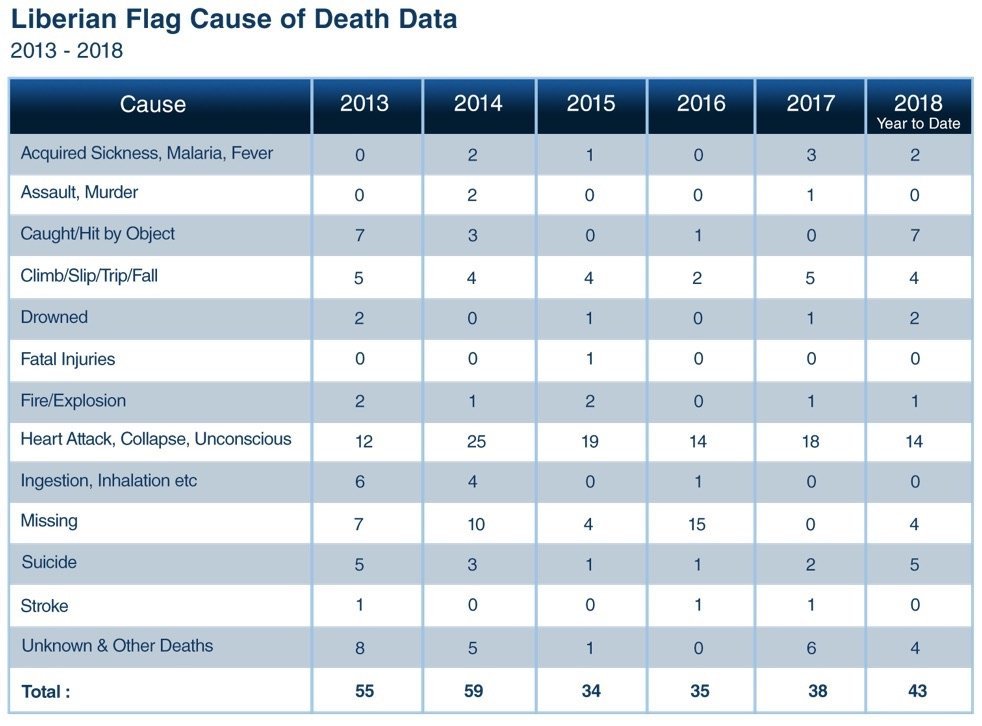

No one expects to go to sea and not return home. Tragically, it is a living fear for those family and friends that every seafarer leaves behind as he or she starts a new multi-month contract. We consider it an inherent and globally shared passion to prevent accidents that cause injury and death. As such, we felt it would be useful to share the following Liberian Flag Cause of Death data we have collated for the last five years so that, we, as an industry, can try to make sense of these facts, figures and trends.

The very nature of shipping, and other industrial jobs, is that the environment comes with risk. Working with machinery, chemicals, fuel, and gasses in unforgiving surroundings means small accidents and oversights can have terrible consequences. Anyone who has served at sea understands this. The climb/slip/trip/fall numbers are a reminder to us all of what can happen when ‘everyday’ mistakes occur.

Seafarer health, welfare, and mental illness has been a regular topic of coverage in the trade press and, from the figures carried above, it appears this is an area that rightly requires attention; it is the largest killer at sea by these records. The occurrence of heart attacks and other similar health-related incidents may not be a surprise given the increasing age of seafarers. To a degree, we are taking common onshore ‘middle-age’ problems to sea.

According to our investigations, it is also likely that many of the missing crew are victims of suicide (though there is not enough evidence to classify their deaths as such). Solving this problem might require a rethink on how we address training and health education for seafarers and masters. Onshore everyone can access doctors, counsellors, and (dare I say it) online information about health issues. At sea things are different and employers and fellow seafarers do have a duty to each other to ‘red flag’ health and mental wellness concerns…because no one else can. But to do this crew must be supported by training and onshore empathy when issues are highlighted.

It is not an enjoyable task writing about what is killing our people. But it is vital that we share and talk about this information, and that we continue to highlight where improvements need to be made. I would encourage you to comment below if you have examples of where and how improvements can be made, and how other companies might learn from initiatives you have taken.

Excellent piece. Thank you, Scott

Very well written

Agreed and thanks Scott for the data, albeit rather morbid.

Scott – May I make a suggestion?

I strongly suspect that your line, “Heart attack, collapse, unconscious” actually combines heart attacks, etc – which do happen – with deaths due to asphyxiation consequent upon entry into enclosed spaces.

Could you separate these out? The results might be valuable.

Andrew, thank you for your comment. You raise a great point and it is especially tragic when the cause of death is related to a widely discussed and mandatorily trained risk, such as enclosed space entry. What strikes me the most about such accidents is when a shipmate goes into an enclosed space to rescue a fallen crewmember, but then becomes a victim him/herself. This innate human instinct to help another sometimes blinds risk to oneself.

With regard to your question, we have listed cause of death in the above table. The deaths that were related to enclosed space entry are in the row titled “Ingestion, Inhalation, etc” as the cause of death in those cases are related to the inhalation of toxins, including CO2 and other oxygen deficient atmospheric gas.

Good to see a ship registry sharing cause of death data. Greater transparency in the industry is much needed if we are to tackle the underlying issues. Hope others will follow suit…

Well written. Having started my sea career in 1982, here is my take:

1) Though technology should have simplified things with better rest hours

and better R&R; it has reduced the same since the no. of personnel have been reduced.

Basically a seafarer is supposed to work like a machine and rest even if he cannot due to various factors.

Ports are especially more bectic due to fast turnaround times and one is supposed to plan out his “rest” which is frequently interrupted due to provisions/bunkers and excessive amount of clerical work (in many cases work of a supdt. Is transferred on board due to internet etc.)

Many HK n Singapore management cos.keep very low victualling allowance.

In long anchorages seaman are not given shore leave due to launch service not being sanctioned.

Reporting against the cos. means blacklisting and seamen then cannot get a job in the future.

There are more points and they basically result in a seaman being treated like an inferior human being resulting in many of the casualties etc.

Great Article Scott! Returning seafarers to their families in the same condition as when they left should be everyone’s priority. Zero accidents/work related fatalities is what is acceptable.

Scott, the Seaman’s Church Institute of NY has been doing good work on addressing mariner suicides. There is a thought out there that higher connectivity with land via social media is, ironically, making mariners feel more lonely being away, as they can constantly see the (best self) version of their friends’/family’s lives back home.

http://www.seamanschurch.org has a joint study/report on how to care for mariner’s mental well being. On the website, its pretty much the first link to get you to article and reports (splash doesn’t seem to let me past the link in here).

Very well structured article.

Hi Scott,

It’s great to read your article. I am a seafarer myself and a father to a seafarer as well. Apart from my sea profession I also worked onshore, the last of which was in the crew management of a very large container company. Currently I work as a part-time Consultant to maritime organizations here in the Philippines and likewise I am connected with a shipmanagement company.

In the long stint of a certain seafarer onboard, it goes without saying that s/he can encounter a lot of professional issues onboard coupled with personal issues or problems s/he may receive, in an instant via sms, facebook, etc., from home. These things heavily contribute to the mental well-being of every seafarer hence a strong possibility that s/he can think of an “outlet” to get rid of it, so to say.

Not a single medical examination, prior shipboard assignment, may determine the mental health of a seafarer. S/he may end up being declared well-fit for the job but it is already a different story while onboard. The manning agent may also carry out a lot of seminars, orientations and advices while a seafarer is on vacation but then, again, it is a different story while onboard.

How do we address that?

We are all aware that there is an onboard management particularly by the so-called top four – the Captain, Chief Officer, Chief Engineer and the Second Engineer. Understand that most who handle these roles nowadays may still be from the old school (s) and they are the ones who may be very strict, disciplinarian, etc., etc., which may end up as being “feared’ by his/her subordinates. And as a result the subordinates may feel that a barrier is within them and they cannot simply approach his/her superiors most especially if a seafarer has a problem, be it onboard or at home.

It’s high time that shipping companies would cultivate the principle of coaching and they MUST start training their top four for this session so they can develop their coaching skills. This is certainly one great tool that any of the top four can bring onboard and regularly schedule each of their seafarer, within his/her department, for a 1:1 coaching sessions. I would say at least twice a month with 2-weeks interval within is okay, the first session could be allowing the seafarer to raise any topic (onboard or at home issues) s/he wants to discuss and the 2nd session for the top four to cite his/her work assessment or evaluation of the seafarer . This way they both “communicate” with each other hence allowing to remove any barrier, in case there is/are any.

On the other hand the Chief Officer and the Second Engineer may be coached by the Master and the Chief Engineer, respectively. The Chief Engineer may be coached by the Master, otherwise each can be coached by their Marine/Technical Superintendents during a visit.

Hope to have shared my thoughts about it.

Aye yours,

Cesar

Scott Hi. Thanks for sharing the info. The article is a very useful compilation of the worst that can happen to a seafarer.

Just an observation – On a quick glance it appears that most of the fatalities appear to be due to sickness or other reasons than those directly related to work.

Have a couple of queries:

1) How would you differentiate between Fatal Injuries and Caught/Hit by Object

2) What was the total no of seafarers in the respective years. This could perhaps give a trend.

Thank you for your questions, Capt Shivangi. The categories identify the cause of death. In the case of the one fatal injury in 2015, it was a complication after the injury that was the cause, so it was difficult to use the other categories.

As for your second question, we do not have the data to provide this detail.

Excellent & well- supported article concerning the most serious topic the maritime industry is facing today.

Hi Scott. I share the comments above in welcoming the article. A couple of points :

1) It would be good if flag states and P&I Clubs could share their data so there is a more accurate picture of deaths especially in relation to suicides at sea

2) My organisation, ISWAN, works with others in trying to improve the mental wellbeing of seafarers. We also have a free global helpline, SeafarerHelp, that provides emotional support to seafarers and their families. Further information is available at http://www.seafarerhelp.org

This is very interesting from a Sociologist’s who specialises in the shipboard work environment perspective. Great to see the Liberian registry not being afraid to show these figures and generating some discussion, despite the limitations. One issues I have noted from my research is that safety still overshadows health, and it is not a matter of semantics, neither can we assume that safety entails health and well. I have found from a few seafarers that safety is much more understood and practiced than health. With the ISM Code being teh dominant [health] and safety system on board, there is still the tendency to neglect health issues. This is also something to think about. Great conversation however!