Why shipping should be worried about soaring ocean temperatures

The past couple of months have seen countless headlines on wildfires and concern about the immense heat on land. Gaining less exposure, but potentially just as severe, have been the record-breaking ocean temperatures registered this year. The world’s oceans have been breaking surface temperature levels almost weekly. Such high temperatures could bring extreme weather to shipping routes and ports and cost the industry billions.

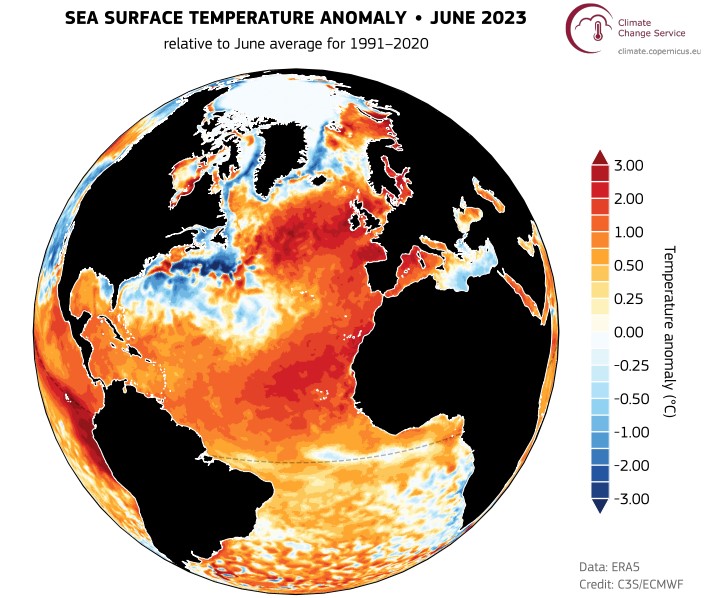

The Atlantic Ocean is getting hotter and hotter. According to the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, the average temperature of the global ocean surface on July 31 was exactly 20.9648 degrees Celsius, narrowly beating the previous record set in 2016. The Atlantic Ocean’s surface temperature however surged to a record 25°C, a whole 1°C warmer than the previous high, set in 2020. And the trend of increasing temperatures is consistently pointing upwards, which will bring more rough seas for shipping to contend with.

“Earth is a physical machine that is always seeking equilibrium, and hurricanes are one of the most efficient ways to distribute heat on a global scale. Unfortunately, they can also be quite destructive and need to be respected,” Jesse Vecchione of Weathernews told Splash.

“A critical temperature in tropical cyclone development that forecasters look for is 27C, and with the global temperature index increasing we can expect to see that threshold exceeded more frequently, and in turn more frequent hurricane development,” he added.

The biggest threat to the commercial shipping sector from the warming seas will be the increased frequency and intensity of weather hazards driven by ocean warming.

These include more intense hurricanes, heavier rainfall and snowstorms as well as shifts in weather patterns so much so that some areas face rainstorms and flooding while others face worsening drought conditions and wildfire risks. There is no need to look further than the drought and water shortages at the Panama Canal which make passage through the canal less reliable and delay vessels.

These changes in weather patterns threaten the entire shipping industry – vessel owners and operators, cargo owners, and ports. There are also knock-on effects on global supply chains that could affect economies more broadly.

Successive winters in the North Pacific have seen many box spill incidents, most memorably the ONE Apus (pictured above), which lost up to $200m worth of containers in late 2020. Weather experts tracking ONE Apus’s path suggest the storm cell it hit could have seen the ship hit by waves as high as 16 m.

It is estimated that one in 10,000 waves is a rogue wave – but while they’ve been the subject of marine folklore for centuries, they were first officially recorded in the 1990s.

Global warming is creating more freak waves, more ferocious and sudden storms far out to sea. Ship designs – and cargo configuration – of the future will need to absorb these fast-changing weather patterns.

The Irish Navy, looking at fleet replacement, is tweaking the design of its future ships because it believes climate change has contributed to far rougher weather and far bigger waves in the Atlantic.

Defined as a wave that’s more than twice as high as the background ocean, rogue waves can reach more than 30 m.

A 2019 study looking at two decades of wave data carried out by the UK’s National Oceanography Centre and the University of Southampton found that the height of the rogue waves was increasing by 1% year-on-year.

Another recent study published by the University of Melbourne, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere in Hobart, and the IHE-Delft Institute for Water Education in the Netherlands simulated Earth’s changing climate under different wind conditions, recreating thousands of simulated storms to evaluate the magnitude and frequency of extreme events.

The scientists claim that if we do not curb global emissions, there will be an increase of up to 10% in the frequency and magnitude of extreme waves in extensive ocean regions.

“The ocean has already absorbed 90% of the heat generated by and roughly 30% of the carbon dioxide emitted by humans burning fossil fuels. Warmer water also expands and raises sea levels as well as holds less oxygen. So, we’re seeing the ocean heat up, lose oxygen, and get bigger. A warming ocean will also supercharge storms,” Sarah Cooley, director of climate science at NGO Ocean Conservancy, explained to Splash.

Her colleague Delaine McCullough, Ocean Conservancy’s shipping emissions campaign manager, warned that vessel owners and operators face risks of delays in departures and entry to ports and more frequent rerouting with accompanying costs, as well as potential damage to their ships and risk to crews.

“Cargo owners’ risks include damage and loss of their cargo, costly delivery delays, and potentially higher demurrage and detention fees,” McCullough said.

Data Ocean Conservancy provided to Splash claims that the total climate risk linked to the impacts of extreme weather on ports could be worth up to $7.6bn each year. In addition to these direct costs, port closures and reconstruction due to storms and other climate hazards put an estimated $67bn of trade at risk annually.

Anaïs Rios, policy officer for shipping and climate at Seas at Risk, alluded to recent research from Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute which estimates that more than $122bn of economic activity including $81bn in international trade is at risk from the impact of extreme climate events per year. And since an estimated 90% of global trade is done via ships, it is no wonder that the figures are so high.

Furthermore, the rising sea levels due to high temperatures might require substantial work on raising the heights of port terminals. Ocean Conservancy noted that raising the height of existing port terminals alone could cost more than $63bn by the end of the century.

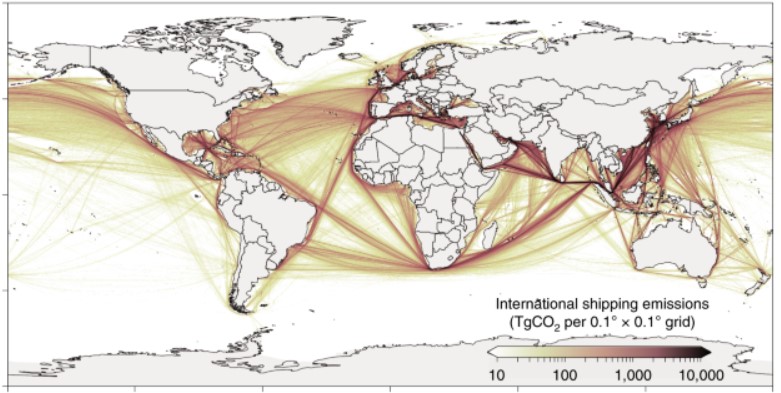

But shipping is also a contributing factor in all of this. Commercial shipping’s use of fossil fuels generates approximately 1bn metric tonnes of greenhouse gases (GHG) yearly, as well as black carbon and soot. Using wind propulsion, slow steaming, developing and deploying zero- and near-zero lifecycle emission alternative fuels will decrease shipping’s GHG emissions considerably.

There is another way maritime shipping is contributing to rising sea temperatures albeit filed under unintended consequences.

The global sulphur cap regulation imposed in 2020 by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) have cut ships’ sulphur pollution by more than 80% and improved air quality worldwide. The reduction has also lessened the effect of sulphate particles in seeding and brightening the distinctive low-lying, disappearing reflective clouds that follow in the wake of ships – so-called ship tracks – and help cool the planet.

The lack of ship tracks warmed the planet up faster and the trend is magnified in the Atlantic, where maritime traffic is particularly dense. In shipping corridors, the increased light represents a 50% boost to the warming effect of human carbon emissions. This was shown to be the case in a paper published last month by Michael Diamond, an atmospheric scientist at Florida State University.

Another way ships contribute to the increased production of GHG is through fouling, a process in which marine plants and animals attach themselves to ships’ hulls. This too is set to worsen as oceans get warmer.

Fouling can damage a ship, increase drag, and its immediate effect is a loss in ship speed at a constant power – or a power increase to maintain a constant speed leading to increased emissions. The accumulated costs of hull fouling can amount to $30bn in business costs, plus millions of tons of CO2 annually, according to studies carried out by class society DNV.

Studies have revealed that a layer of slime as thin as 0.5 mm covering up to 50% of a hull surface can trigger an increase of GHG emissions in the range of 20 to 25%, depending on ship characteristics, speed and other prevailing conditions.

More severe biofouling conditions can lead to higher emissions. With a light layer of small calcareous growth like barnacles or tubeworms, an average-length container ship can see an increase in GHG emissions of up to 55%, dependent on ship characteristics and speed.

Crucially, the fouling problem gets worse for vessels idling in warmer waters. Also, with ocean temperatures rising on a global scale, biofouling hotspots are increasing in size and severity, leaving more ships at risk of the negative impacts of biofouling on ship efficiency, according to a recent study by I-Tech, a Swedish developer of antifouling products.

Since fouling species flourish in warmer waters, the risk of them making a home on ship hulls is significantly increasing year-on-year.

Trying to put some positive spin on the changed climate in concluding, Vecchione from Weathernews told Splash: “The trendsetters should see an opportunity. With increased temperatures shipping passages north of Russia and Canada should become more frequent. This will lead to a vast improvement in emissions as voyages will be much shorter.”

If only we had been warned about ABW & ACC earlier!

If only we had been warned about AGW & ACC earlier!

May I say how very much I admire this article?

You’re allowed to gush, sir!

Thank you for the kind words.

Soaring he says! SMH…

thank you for publishing this article, it explains very clearly part of the way that global warming will affect shipping, in additional to slowing and stopping the Gulf Stream which would create a new ice age, the rogue waves and additional cyclones… Please continue to explore and explain every nook and cranny of our industry. Far too many people have no comprehension of what effect GHG emissions have on global warming and why, and what the problem is with global warming (yes- melting ice caps are easy examples).