Fiercely hot summer takes its toll on river transport worldwide

This year’s record-breaking heat in the northern hemisphere’s summer and lack of rainfall has seen a reduction in water levels around the globe, impeding river transport of grain, diesel, coal and other commodities, which is driving up costs and making material supplies scarce.

An unsettling drop in water levels in key European waterways has resulted in immensely strained logistics in shipping commodities throughout the continent, with barges only able to carry one-third or one-quarter of their usual cargo.

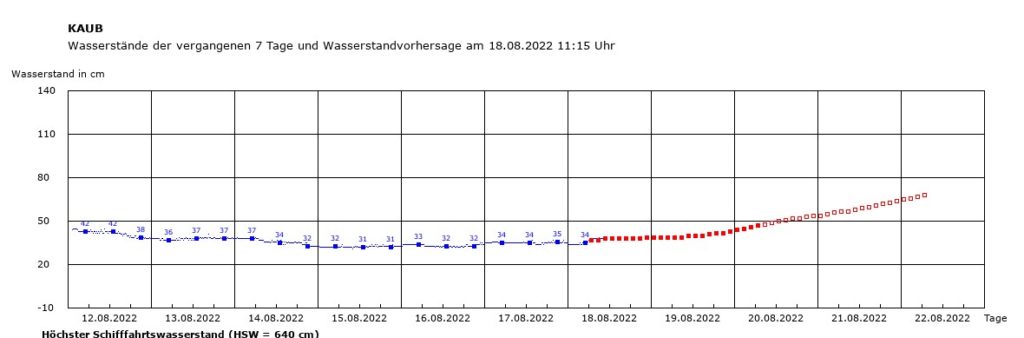

Germany’s Rhine river made most of the headlines after a water marker at Kaub, west of Frankfurt, dropped to an extremely low level earlier this week, threatening barge traffic on a crucial conduit for chemicals and grain as well as commodities, including high-in-demand coal, as the country races to fill storage facilities ahead of the winter.

“Barge situation is becoming more critical as water levels on the Rhine continue to drop. Measuring point Kaub reports water levels below the 40 cm mark, making barge transport impossible to and from many locations. This is putting additional strain on other modes of transport and additional delays are inevitable at this point,” liner Maersk noted in its operational update earlier this week.

Xclusiv Shipbrokers warned in a recent update that the Rhine situation could severely restrict the flow of coal, fuels, and other commodities for months, increasing the price of EU natural gas to above €200/MWh, not far from an all-time high of €300 in March. The report also suggested that goods could be transported either by road or rail, but at a much higher cost.

We expect low water levels to shave off at least 0.5% of German GDP growth in H2

Meanwhile, UK shipbroker Simpson Spence Young (SSY) found that with barge availability tightened further by some barges diverted to the Danube to carry Ukrainian cargoes into Europe, Germany’s coal-fired generation could be at risk. Utility Uniper has already warned of output cuts at two of its coal-powered plants due to supply shortages.

With coal barges sailing at reduced loads, a professor of international economics at the University of Amsterdam, Sweder van Wijnbergen, said Germany could have an energy problem if the situation persists for a long time.

The Rhine is an important link between industrial producers and global export terminals at North Sea ports such as Rotterdam and Amsterdam, while canals and other rivers link the river to the Danube, making it possible to ship to the Black Sea as well. About 300m tons of goods and products are shipped from the Rhine each year, making up 80% of water transport in Germany.

“It is only a matter of time before plants in the chemical or steel industry are shut down, mineral oils and building materials fail to reach their destination, or large-volume and heavy transports can no longer be carried out,” Holger Lösch, deputy director of the Federation of German Industries, cautioned after chemicals companies such as BASF warned low Rhine water levels are expected to increase costs and could lead to production cuts.

Germany’s government is looking for ways to deepen the river at strategic points, with the country’s transport minister, Volker Wissing, saying this week that more investment is underway in the rail and road network.

“The navigation channel there urgently needs to be deepened so that it is possible to keep inland shipping running even at low water levels,” Wissing told local media. Deepening the channel would take until the early 2030s and cost about €180m ($183m).

Commenting via LinkedIn, Kris Kosmala, a partner at Click & Connect, said: “The larger issue of dredging needs to be questioned, as a deeper river bed doesn’t mean there is more water for sailing. Agriculture, cities and industries depending on water take water from Rhine and tributaries, so increasing population and agro-industrial activity upstream simply consumes more water, leaving less downstream for sailing. So, this season, like the summer of 2018 will simply mean more shipments by rail.”

Mark van Koningsveld, professor of ports and waterways at the Delft University of Technology, told Splash that dredging is not a short-term solution for Germany due to hard rock formations, unlike Romania and Bulgaria. “What are effective interventions in the river system depends on local circumstances,” he remarked.

For van Koningsveld, what we are seeing now is basically a short-term response, which in some cases means increasing prices or reducing loading rates.

“If you want to prepare better for these kinds of situations in the future, then basically what you need to do is to get a better grip on your water system to ensure that during low water discharges, which seem to be more of a regular thing, you can still have sufficient water levels,” he said.

The Rhine situation adds to the long list of risks and challenges confronting the German economy and makes a recession in the second half of the year almost certain, according to Carsten Brzeski, global head of macro at Dutch multinational banking conglomerate ING.

He suggested that the current disruption could be greater than during the last serious stoppage in 2018.

“Back in 2018, low water levels shaved off some 0.3 percentage points of German GDP growth over two quarters. However, back then, the low water period only came in late September. To make things worse, waterways are essential for coal transportation, which in turn is needed to offset less gas from Russia. This means that unless the weather brings any substantial relief, the low water levels will do more economic harm than in 2018. We expect the low water levels to shave off at least 0.5 percentage points of GDP growth in the second half of the year,” Brzeski said.

Normally, the lowest water levels are only reached in September and October

Ships are still running on the Rhine and the traffic has not come to a complete standstill. A glimmer of hope is the rain forecast for Germany, which should, according to the latest government data, lift the water level at the country’s key waypoint above a critical level this weekend. The marker at Kaub is expected to reach up to 53 cm on Saturday and rise to 63 cm late on Sunday.

The phenomenon facing the Rhine is common across much of Europe. In the UK, the driest July in over 80 years has largely evaporated the source of the River Thames. Water levels in Italy’s longest waterway, the River Po, have sunk to record lows, threatening food production, and water levels in France’s Loire are also close to record lows.

Hydrologist Niko Wanders of Utrecht University said he has never seen a drought so extreme and so widespread across the continent. “It’s exceptional because it’s all coming at the same time. And it’s only August. Normally, the lowest water levels are only reached in September and October,” he commented.

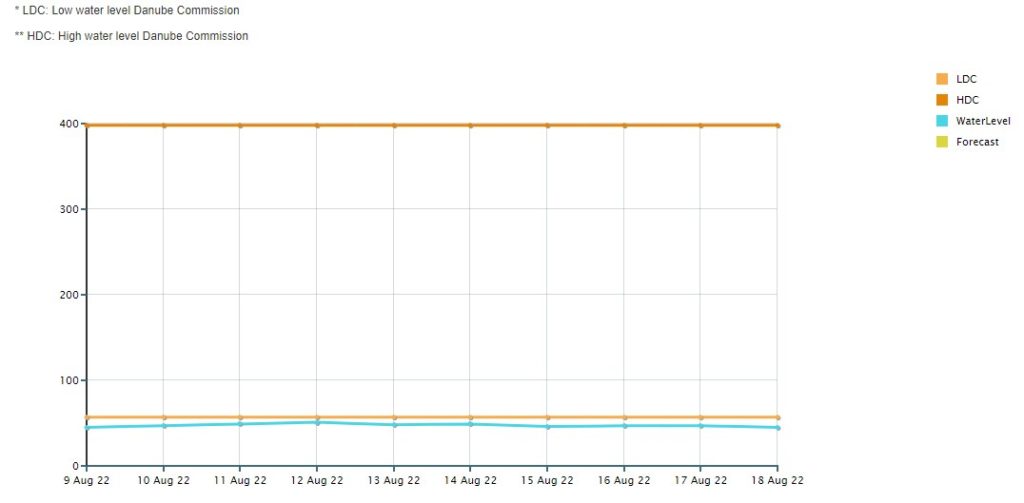

Western Europe’s longest river Danube, a trade and transport artery that passes through ten countries, has also seen a reduction in water levels in its delta, limiting grain and vegetable oil shipments as large vessels are restricted from river ports. Data from the Danube Fairway Information Service Portal shows the water level at Tulcea, close to where the branch of the river on which Ukraine ports are situated meets the main body of the Danube, fell from a low water level standard of 57 cm to 45 cm on August 18.

With Ukraine’s Black Sea safe corridor agreement prioritising grain shipments, the Danube ports of Reni and Izmail remain the primary outlets for sunflower oil exports, and vessel size restrictions are already being imposed. The movement of barges navigating to and from Constanta port, which has exported close to 1.5m tonnes of Ukrainian grain since February, is also being restricted or limited.

“The reduced draft is forcing river barges to part-load, slowing the movement of grain and other commodities,” UK shipbroker Simpson Spence Young (SSY) noted in its latest report.

In Serbia, dredging is underway to keep the Danube waterway open, with water depths reported at no more than waist high across almost half of the river’s width in Novi Sad. The water depth is estimated at less than half the usual August level on the Danube and its other major waterway, the Sava River, impeding the transportation of coal.

Meanwhile, China is experiencing a severe drought along the Yangtze River, which could last until September as local governments race to maintain power and find fresh water to irrigate crops ahead of the autumn harvest. A massive heatwave has now lasted more than two months across the basin of China’s longest river, which supports roughly one-third of the country’s population, cutting hydropower supplies and parching vast swaths of arable land.

The southwestern region of Chongqing, which contains the majority of the Yangtze’s Three Gorges reservoir, is scrambling to secure power. According to local media, companies with operations in Sichuan, such as CATL, the world’s largest battery maker, and Toyota of Japan, have suspended production in the province as a result of the restrictions.

Rainfall is expected to remain low until the end of this month and beyond, according to the Ministry of Water Resources. Water levels on the main trunk of the Yangtze, the world’s largest cargo inland waterway by volumes shipped, are now at least 4.8 m shallower than normal, and the lowest on record for the period, officials said.

Although official records show the declining water levels along the Yangtze are yet to impact navigation services, with the first seven months of this year seeing an increase in throughput at major ports along the river, Chinese officials have cautioned that a threat is imminent if drought conditions remain severe.

Concerning the current pressing issue on the Rhine, professor van Wijnbergen stated that if summer sailing restrictions are a foreshadowing of the future, “perhaps the Rhine will not always do what the European Commission wants,” referring to plans to boost inland shipping.

Patrick Verhoeven, managing director of the International Association of Ports and Harbors (IAPH), told Splash that a series of regional workshops they conducted on infrastructure gaps identified the critical situation of inland water infrastructure in some parts of the world.

Nobody can deny climate change anymore. So inland shipping has to adapt to this

“Funding is an essential issue and it is one of the reasons we are promoting the development of a market-based measure for shipping decarbonisation that would generate revenue that could be used for the upkeep of port and waterborne infrastructures. Meanwhile, there is an urgent need to address underinvestment in rail infrastructure as well as making zero carbon fuels available for trucks,” Verhoeven said.

For van Koningsveld, on the one hand, people were looking at inland shipping as part of the solution in terms of climate change and were pushing more cargo to the water as a means of reducing emissions, but droughts and energy crises have made that less easy to achieve.

“In the long term, you should look at how important inland shipping is for your entire cargo transport system and then try to optimise that. At the moment, it is what people call the perfect storm of all these factors that are acting simultaneously. That is, of course, quite unfortunate, but that should not be the basis of a really long-term policy,” van Koningsveld suggested, pointing to the Dutch high-water policy of infrastructure planning of 50 to 100 years.

Among shipping lines learning to adapt to trickier inland voyages is Germany’s HGK Group, whose unit HGK Shipping operates more than 350 barges along the Rhine, and has been developing low-water ship types for the past five years.

“Nobody can deny climate change anymore. So inland shipping has to adapt to this, which is what we are already doing at HGK,” a spokesperson for the company told Splash.

HGK’s Gas 94 barge design can still transport 200 tons of liquefied gas on the Rhine even at a critical level of 30 cm at Kaub. This is made possible by the optimised buoyancy properties of the ship’s hull. At 12.5 m, the 110 m long gas tanker is also wider than the usual ships in the HGK Shipping fleet.