‘Pancaked’ bridge wedged in mud hampers Baltimore salvage ops

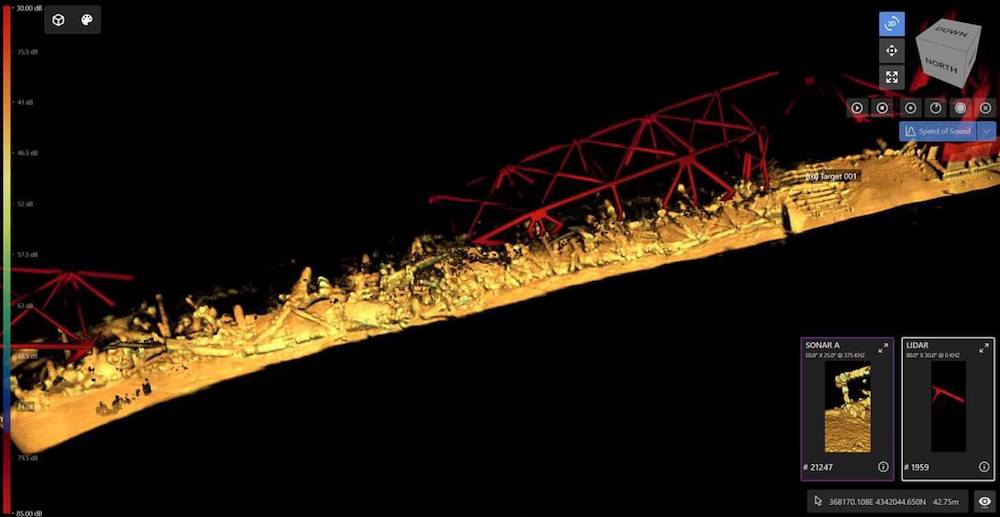

Sonar images released yesterday show the magnitude of the job that divers and salvage workers face as they begin to remove the wreckage of the Francis Scott Key Bridge strewn across the main shipping channel into the port of Baltimore.

Eight days on from the moment the 9,962 teu Dali containership rammed into Baltimore’s largest bridge, destroying it and killing six road maintenance workers in the process, the treacherous conditions on the bed of the Patapsco River are coming into blurry focus.

A second temporary alternate channel was opened yesterday on the southwest side of the main channel near Hawkins Point in the vicinity of the Francis Scott Key Bridge for commercially essential vessels. The channel has a controlling depth of 4.27 m with plans underway to create a deeper third channel with depths of more than 7 m.

“Our number one priority remains the opening of the deep draft channel. We are simultaneously focused on opening additional routes of increased capacity as we move forward,” said US Coast Guard commander Baxter Smoak.

Maryland governor Wes Moore said rough weather conditions this week, including thunderstorms, have made it unsafe for divers.

US Army Corps of Engineers colonel Estee Pinchasin said the underwater conditions are “extremely unforgiving” for divers.

After days of bad weather, the water itself is so cloudy and dark, divers can only see a metre in front of them. Shining an underwater light only reflects back like a snowstorm making photos or video nearly impossible.

Sonar images show the bridge’s enormous centre span is buried deep into the soft mud of the riverbed across the main shipping channel.

“What we’re seeing in the water is the wreckage has been has been completely collapsed. Some people use the term pancaked,” Pinchasin said.

A pancake collapse refers to a structural collapse where the collapse occurs from the top down as upper parts of a structure or building settle into lower parts.

“It’s not just sitting on the seabed, it’s actually below the mud line,” said Pinchasin at a press conference yesterday, describing the hard to remove 366 m long centre span. “The state of that wreckage makes it very difficult to figure out where to cut, how to cut, in order to put it into bite-sized pieces.”

Rather than cutting the mangled metal on the riverbed, which is likely to be deemed too dangerous an operation, plans are being drawn up to lift the structure whole.

The head of Lloyd’s of London warned last week that the Dali could prove to be the largest marine pay-out in insurance history.

The ship has been aground for the past week with a section of the structure weighing on its bow. As much as 4,000 tons of steel from the bridge’s frame are hanging on the bow of the ship, pinning the hull to the river bed below.