Swedish scrubber discharge study makes case for stricter regulations

Some 42 months after the global sulphur cap became law, researchers continue to uncover the enormous damage scrubbers are doing to the world’s oceans.

A new study from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden focusing on four ports calculated that water discharged from scrubbers accounted for more than 90% of the contaminants found in water samples.

“The results speak for themselves. Stricter regulation of discharge water from scrubbers is crucial to reduce the deterioration of the marine environment,” said Anna Lunde Hermansson, a doctoral student at the Department of Mechanics and Maritime Sciences at Chalmers.

Traditionally, environmental risk assessments (ERA) of emissions from shipping are based on one source at a time. For example, the ERA might look at the risk from copper in antifouling paints. But as with all industries, shipping is an activity where there are multiple sources of emissions.

“A single ship is responsible for many different types of emissions. These include greywater and blackwater, meaning discharges from showers, toilets and drains, antifouling paint, and scrubber discharge water. That is why it’s important to look at the cumulative environmental risk in ports,” explained Lunde Hermansson who, with colleagues Ida-Maja Hassellöv and Erik Ytreberg, is behind the new study that looked at emissions from shipping from a cumulative perspective.

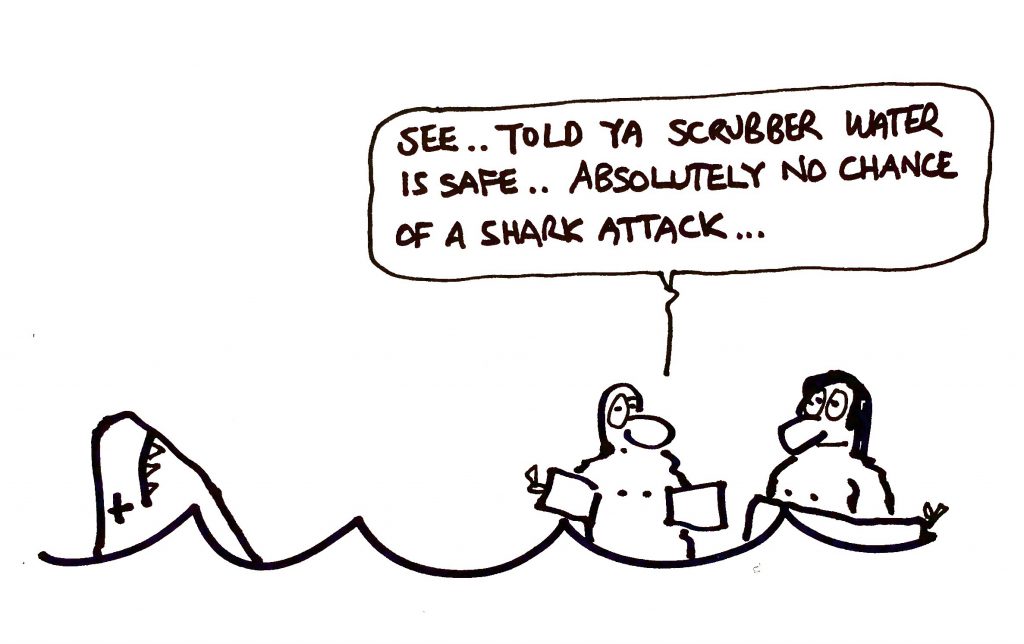

Scrubber water not only takes up the sulphur from a ship’s exhaust gases, leading to acidification of the scrubber water, but also other contaminants such as heavy metals and toxic organic compounds get mixed in. For open-loop scrubbers, which form the majority of kits sold around the world, the contaminated scrubber water is then pumped directly into the sea.

“There is no cleaning step in between – so up to several hundred cubic metres of heavily contaminated water can be pumped out every hour from a single ship. Although new guidelines for ERAs of scrubber discharges are in progress, the ERAs still only assess one source of emissions at a time, which means that the overall assessment of the environmental risk is inadequate,” said Lunde Hermansson.

In this new study, the researchers at Chalmers looked at four different types of port environments to determine contaminant concentrations from five different sources. Actual data from Copenhagen and Gdynia were used for two of the ports. They were selected due to high volumes of shipping traffic, and a substantial proportion of these ships having scrubbers.

The results showed that the cumulative risk levels in the ports were, respectively, five and thirteen times higher than the limit that defines acceptable risk.

Port descriptions used internationally in ERAs were utilised for the other two port environments. One of these environments has characteristics typical of a Baltic Sea port, while the other represents a European port with efficient water exchange due to a large tidal range.

More than 90% of the environmentally hazardous metals and PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) in the samples taken came from scrubber discharge water, while antifouling paints accounted for the biggest load of copper and zinc.

“If you look at only one emissions source, the risk level for environmental damage may be low or acceptable. But if you combine multiple individual emissions sources, you get an unacceptable risk. The marine organisms that are exposed to contaminants and toxins don’t care about where the contaminants come from, it is the total load that causes the damage,” said Lunde Hermansson.

The only port environment that showed an acceptable risk in the researchers’ ERA was the model with the highest water exchange per tidal period, meaning that a high volume of water is exchanged in the port as the tide moves in and out.

The Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management and the Swedish Transport Agency have submitted a proposal to the Swedish gGovernment to prohibit the discharge of scrubber water into internal waters, joining a host of other countries who have instituted scrubber water discharge bans.

The latest data from Clarksons Research shows more than 5,000 ships – around 5% of the global merchant fleet – are now kitted out with scrubbers.

A study from April 2021 found the the country with the highest concentration of scrubber washwater per sq km is Singapore, five times higher than second placed Jordan. Even though the Southeast Asian republic has banned the use of open loop scrubbers in its waters, it is a victim of geography, being at the confluence of global trade.

While scrubbers have been pilloried repeatedly for their acidic discharges into the water studies from NASA last October suggested the the 2020 global sulphur cap had improved atmospheric conditions. The study from the American space agency found that so-called ship track clouds dropped dramatically in 2020, the first year of the implementation of the fuel regulations that saw sulphur content slashed from 3.5% to 0.5% for the majority of the global fleet not using scrubbers.