The case for offshore container ports

Rafael Zarama argues box ports should be established further out to sea.

Container ports have evolved significantly since their inception in the 1950s. These ports, where ships dock in protected coastal waters and cargo is unloaded using cantilever cranes on skids, have undergone changes in size, technology, and optimisation. However, despite these adaptations, the traditional design falls short in providing effective solutions for crucial aspects such as high performance, expansion, environmental sustainability, climate change resilience, port congestion, shallow depths, and the accommodation of larger vessels.

In stark contrast, shipping companies have successfully addressed their efficiency and decarbonisation challenges through the implementation of megamax ships, with a capacity exceeding 20,000 teu. Regrettably, ports have not kept pace with this transformative trend, resulting in a limited number of ports capable of accommodating these colossal vessels. Hindrances like lower bridge heights in the US and width restrictions of the Panama Canal further impede the access of megamax vessels to east coast ports.

The exorbitant costs associated with dredging, protective infrastructure, and equipment pose a significant financial burden, necessitating substantial cargo volumes to recover investments while simultaneously exposing stakeholders to substantial risks. Paradoxically, it is shipping companies that wield the power to determine the survival of ports, a situation that should ideally be rectified, with each country striving to possess sustainable capacity for receiving ships independent of shipping companies.

The current global landscape is characterised by unbelievable challenges and remarkable advancements. The term unbelievable is emphasised to underscore the extraordinary nature of the disruptive and sudden changes we are currently experiencing. As a result, the need for swift adaptation has become more pressing than ever before. However, the port industry, despite operating within a framework of stringent environmental regulations and grappling with limited space, persists in adhering to an outdated adaptation approach. It is evident that continuing down this path is a dead end, necessitating a paradigm shift.

In contrast, the oil and wind energy sectors provide inspiring examples of industries that have ventured beyond terrestrial boundaries and expanded into the ocean. Paradoxically, the port industry remains tethered to the land, investing significant efforts into bringing ships to the shore instead of reaching out to them by sea. It is imperative that ports follow the bold example set by the oil and wind energy sectors and wholeheartedly embrace offshore solutions for container ports.

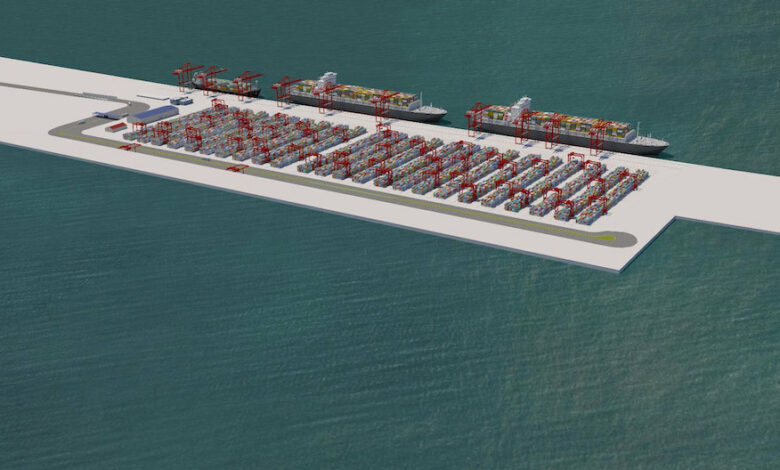

Offshore ports offer an array of advantages. Unconstrained by depth limitations, these ports can be standardised and modular, facilitating efficient handling of ships from multiple directions with a higher density of robust cranes. Consequently, manoeuvres become faster and safer, while ship stability is enhanced in intermediate water areas. Offshore ports significantly reduce the risks of collisions and grounding incidents, expanding the capacity of existing ports and creating additional space for smaller ships operating as cabotage and feeder vessels.

The standardised nature of offshore port concepts expedites processes such as environmental licensing, financial feasibility assessments, and technical evaluations. This standardised approach leads to greater cost-effectiveness and adaptability to specific conditions. Additionally, the compact and prefabricated nature of offshore concepts results in reduced capital expenditure. By incorporating a higher density of cranes and enabling ease of manoeuvrability, offshore ports ensure enhanced performance, leading to greater returns on investment and reduced risks, all while minimising their environmental impact. These systems foster the design of new maritime routes and logistics nodes, including the possibility of a circular route encompassing the Pacific Basin or the establishment of large hubs within the United States.

Not wrong. However, you’re missing one single point : movements. Where traditional ports are mostly settled in sheltered areas, your offshore port does not seem to properly address the need for cargo vessels to lie alongside with minimal movments. Offshore ports will be exposed to higher swell, stronger winds with all the consequences on tug capability, crane operability, not to mention the overwhelming impact on mooring lines and bollards.

The final cost to protect the vessels from weather, sea, current in these ports is already dictating what can be done.

Thank you, Capt. Ships with a length of 400 meters and a deadweight tonnage of 230,000 in intermediate waters are extremely stable. The stormy waves near the coast are more dangerous than those further offshore. The wave capable of moving a megamax vessel does not exist in intermediate waters. The wind is more hazardous along the coasts. The mooring systems used in the offshore oil and gas industry are highly advanced.

And how is the cargo moved on/off shore? Most of it will need to go inland by rail or truck.

it would be interesting to see the underpinning economics of this sort of concept.

This looks like a flight of fantasy.

It’s common for onshore ports to have a bridge connecting the dock with the storage yards. In this case, the bridge could be longer or even maritime using barges. It’s an exercise in optimization based on continuous systems on rails or conveyors. Everything that exists today began as a fantasy.

Good point, Phil . . . a second handling of containers to move from the offshore port to the inland transportation system (inland waterways, rail, or truck), i.e., more logistics bottlenecks, redundant shipping costs, etc

Every system has a cycle supported by transportation systems. Distances and speed do not determine the system’s throughput. Instead, frequency and flow rate are determining factors. Continuous systems are the solution, just as many industries have developed them.