Why investing in dry bulk companies is a bad idea

Pierre Aury revisits a popular topic for his latest monthly column.

Back in February we painted a dire picture of dry bulk listed companies. We looked at their accumulated deficit at the end of December 2020. Collectively our sample of 10 companies had accumulated then $9.5bn of losses since their respective IPOs. As a reaction to that article we got a number of fair comments, especially around the fact that at the time of writing the article the 2021 accounts were available and were showing a massive improvement compared to the end of 2020 numbers. Fair point in fact we should probably have talked about a nadir being reached in terms of accumulated deficit in 2020. Point taken so we will start this article by updating the numbers to include the 2021 and 2022 annual accounts. The following graph shows each company’s accumulated profit or deficit at the end of 2022 (or at the time of going bankrupt, delisting or moving away from dry bulk shipping) in millions of dollars.

The accumulated deficit is indeed down at $5.8bn from $9.5bn. Taking away the Dryships, Scorpio and Paragon disastrous numbers the remaining listed companies have now a reduced deficit accumulated since listing of $418m which is 10 times less than at the end of 2020. A great thank you to the good market of 2021 and 2022. In addition three companies are now in the black over the period: Star Bulkers and Golden Ocean have joined Safe Bulkers in the black.

Another comment was made around the fact that making a fixation on earnings was wrong as investors don’t make money solely through dividends but make in fact a fair share of their profits through capital gains – ie buying shares low and selling them high. Fair point as well so we will look now at how the shares of the companies from our sample have fared over time. Maybe indeed investors who have not made money being paid dividends have actually made money buying and selling shares of these companies. A simple method would be to look at the share prices of these companies today versus the IPO prices as an increase would be indicative of at least a potential for profit. But comparing the share prices today with the IPO price is in fact comparing apples and oranges. Why is that? Simply because all these companies except two have been at various stages members of the not-so-exclusive club of companies with penny shares: most exchanges have rules regarding minimum share price like the $1 rule for the US exchanges. Simply put if the share price of a company goes below $1 the exchange gives a notice to the company to restore a share price above $1 failing which the shares will be delisted.

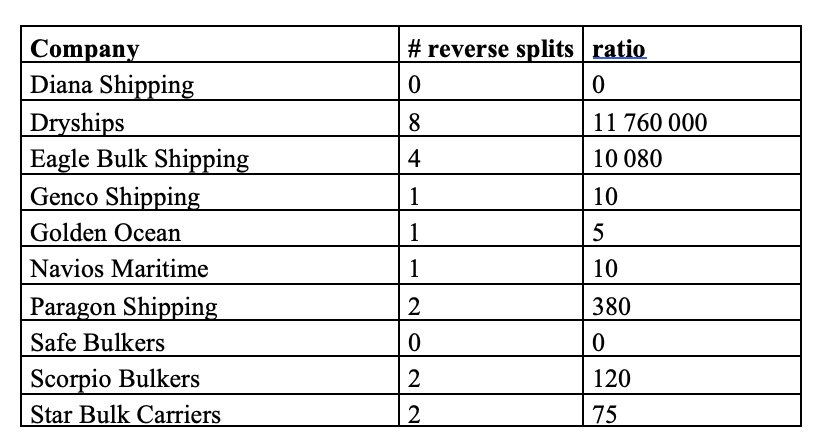

Enter the reverse split. What to do to comply with, say, the $1 rule? Simple you exchange two $0.50 shares for a new $1 share and Bob’s your uncle. In a market dropping like a stone however the newly created $1 share will trade at $0.75 the next day. This explains why some companies had a string of reverse splits. You have to admire the ability of the financial world to coin expressions like reverse split! Why not a share merge? In fact a share split is a sign of success: a share with a price that is too high usually see a liquidity drop in its trade. In order to restore liquidity the share is then split into lower-price shares restoring liquidity. Merging shares is therefore a sign of failure but the financial industry cannot fail hence the use of the reverse split expression keeping the word split which denotes success. On the same topic, it is funny that the financial market is never going down, they merely experience corrections. It is important to keep in mind that financial markets are hard-wired on the long side. Going back to our reverse splits for dry bulk listed companies the following table gives the number of reverse splits that took place for each company and the resulting ratio between the original share issued at the IPO and today’s share. Brace yourself!

At the time of the Dryships delisting nearly 12m original shares had been merged to make one share trading then. In order to compare today’s share price with the original IPO price one needs to divide today’s share price by the above ratio and then compare the result to the IPO price. We will be kind and not do that. Instead, we will use another method which is to see the value today of $10,000 invested at the time of the IPO. The following table gives the result in percentage drop as of mid-July 2023:

So the surviving companies of our sample are going into what is looking like a prolonged patch of bad markets having made no money over a very long period of time and having returned an average -70% for every $10,000 invested in them since IPO.

How can these companies get away with these results? Well, probably through the use of a cocktail of meaningless acronyms like EBITDA and deceiving words like extraordinary items or non-recurring items when reporting their earnings with of course the help of the gullibility and the greed of investors. Investors who would have made a fortune short selling these stocks. But, hey, things always go up in financial markets.

I have an investment advisor, who doesn’t buy stocks that have performed poorly in the past. On the other hand, I believe that “past performance is not an indicator of future results” and each poorly performimg stock needs to be evaluated on its own merits.

In this vein, I am sitting on a 40% gain in SB and have done the same in other industries.

It would have been useful if the author of this article had evaluated the current dynamics and economics of the shipping companies, in order to make an evaluation about the FUTURE. The PAST is interesting but you can’t make money in the past.