The rise and fall of Vale as a shipowner

The rise and fall of Vale as a shipowner stands as another cautionary tale in the long line of failed industrial shipping plays.

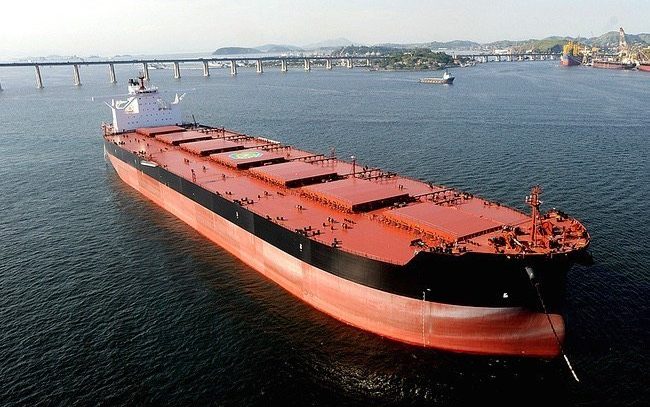

The global financial crisis and a failure to navigate Beijing’s power hierarchy consigned the fleet of 400,000 dwt ore carriers, the biggest bulkers ever built, to economic oblivion.

Vale announced this week it had sold another two of these giant ships – the largest bulkers ever constructed – to China’s Bank of Communications, leaving it with just two left, which are also due to be sold soon.

Vale’s dabble with shipowning follows a a well-worn industrial path, most notably the oil majors and their huge build up of tankers in the 1970s, many of which headed straight to the Norwegain fjords into lay-up, only emerging to either sell to the breaker’s yard or be picked up by Greek shipowners – or savvy US hoteliers in the case of Loewes Corporation – at scrap related prices.

Roger Agnelli, the former CEO of Vale, came up with the valemax concept 10 years ago as a way to claw back pricing power with Australian mining rivals. Freight costs a decade ago – the highest of all time – were making Brazilian ore uncompetitive. Brazil lies 45 days steaming away from key customer, China, compared to Australia’s comparatively nearby 10 days.

Vale started to place orders for this brand new class of ship in 2008 anticipating 40% savings over the hot cape spot market.

At the time Vale’s intercontinental iron ore conveyor belt concept had shipowners on edge. Its fleet plans formed major planks of most shipping conferences nine years ago. However, the collapse of the dry bulk freight market quickly saw the ships – ordered at an average price of $126m – slide in value by around 40%, while the cape spot market fell off a cliff from six-digit a day highs to less than $10,000.

Vale’s capital cost advantage was already in tatters, but things were set to get a whole lot worse for these cursed ore carriers as China, Inc threw in an unforeseen curveball.

Citing safety concerns following a crack on the maiden voyage of the 362 m long Vale Brasil in 2011, China moved to ban direct valemax calls. In reality, Beijing was heeding the calls of local shipowners and steel mills who were worried at the possible stranglehold Vale could hold in the ore markets.

The Brazilian miner was forced to create two ore transhipment hubs in Malaysia and the Philippines where cargoes were shifted onto smaller tonnage for onward shipment to China. The valemax experiment had been holed below the water.

The end game for these ships – one symbolic of the maritime rise of a new superpower this century – was China taking them over in return for direct access to its ports, something Panos Patsadas, from brokers Target Maritime Transport, told me yesterday was the perfect game of shipping chess. Check mate!

HELLO SAM – This is an excellent concise summary that actually could be used as a sort-of-template for many a venture that seemed at the time to be a good idea but ultimately crashed & burned. Think Big and change the course of history … or go down in flames! It reminds me of our 1988 foray into the automated container storage system that we named Computainer … from the outset, some said that it was a great idea … decades ahead of its time!

CFN – BMJC http://www.earlsindustries.com

A more apt title would have been ‘The rise and rise of China’