Are panicked, overbuying American shippers the reason for today’s container crisis?

Around a fortnight ago an agitated head of supply chain for one of the world’s largest BCOs rang Splash. The executive – responsible for shipping more than 60,000 feu on the transpacific – was adamant that the narrative with this year’s supply chain chaos was all wrong.

The elephant in the room with the box buildup across US coastlines is not what is generally being reported, the supply chain chief claimed. The real cause of the problems has been massive over-ordering by panicked shippers.

“If there were real shortages as many would have you believe how come every warehouse in the US is full to the rafters? Panicked overbuying, questionable forward sales predictions and weak, none too transparent procurement systems among American shippers are in fact the greatest reasons for this year’s supply chain disaster,” the Asia-based supply chain veteran, who preferred to speak on condition of anonymity, told Splash.

So is the case? It’s not the liners at fault, not the archaic US port and intermodal infrastructure as the main culprits for 2021’s extraordinarily strained global container structures? Splash sought the verdict of experts from around the world to deliberate the matter.

Bjorn Vang Jensen, vice president at consultancy Sea-Intelligence, concedes that factors like panic buying, highly inaccurate sales forecasts, and a tendency to regard data sharing as risky and expensive, have played a role in the global supply chain meltdown.

However, these are all issues that have existed everywhere and forever, also long before containerisation, he points out.

“In the past, almost any supply chain has been able to roll with such punches, which are now mostly forgotten as minor blips in a dusty dataset,” says Jensen, whose past career including lengthy stints at Maersk and then on the other side of the negotiating table at Electrolux.

“What you see today is not only a black swan event, but in fact an entire bevy of black swans, and one which grows larger by the day, as more and more weak strands in the supply web snap,” Jensen says.

The US is indeed the real origin of this fiasco, the Dane agrees. Yet, he has answers to why warehouses are so full.

According to Sea-Intelligence research, many industries in the US are actually dangerously low on inventory.

Another explanation is the very real shortage of drivers to take goods from those warehouses that are actually full, to the consumers.

A game of musical chairs

Steve Ferreira, CEO of New York-based Ocean Audit, describes today’s clumped box situation as like a game of musical chairs.

“You don’t want to be left standing without a seat, and it’s a self-perpetuating cycle,” Ferreira says, giving a couple of recent examples such as Walmart ordering 149 containers of garbage cans on one single vessel or a French tire manufacturer inking a new charter to Houston.

“How are Michelin’s tires going to supply cars you can’t buy due to a chip problem?” Ferreira muses.

Andy Lane from CTI Consultancy, a container advisory, cites both archaic US logistics infrastructure as well as the near impossibility for retailers to have prepared for such a see-saw in demand as Covid presented as the two largest factors in today’s snarled container situation.

“US supply chains and logistics systems are frail, but to balance that, no one would ever maintain more than say 15-20% capacity latency, which would be cost prohibitive in normal times,” Lane says.

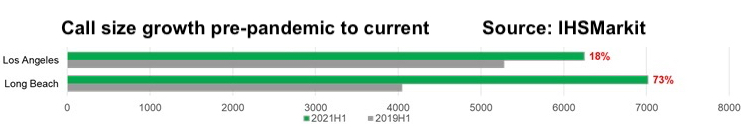

Ports cannot keep up with the pace of increased import demand over a sustained period, neither can intermodal capabilities and lastly warehouses and DCs.

“The entire system grinds to somewhat of a halt, because it was never going to be capable of absorbing a 20-30% or more increase in consumer demand,” Lane says.

Having said that, Lane does see a huge void in planning and communication across all segments of the supply chain.

“The shippers/importers have tried to import more than their DCs and distribution capacity can handle,” Lane says, adding: “The carriers have tried to move more demand than they should have known that the ports and landside can accommodate. Adding more floating capacity and container fleet is pointless if it creates a bigger gridlock.”

This has resulted in massive wasted resources. “As a complete collective, all supply chain stakeholders have simply ignored constraints, and just unintelligently flooded the system to everyone’s detriment,” Lane maintains.

Of all the capacity deployed on Asia-North America west coast in 2021 so far, 19% has been lost to congestion, and the figure increased to 24% in August, according to data from Sea-Intelligence.

Liners playing games

Kris Kosmala, a Splash columnist and partner at advisory Click & Connect, reckons shippers have not been panicking. They’ve been played by the liners, he argues in conversation with Splash.

“It all went bad with irregular sailings when carriers cut capacity in response to Covid fears,” Kosmala recounts. This deprived shippers of the regular services on which they built their supply chains execution. So, they ordered more and those orders accumulated in containers waiting for slots which were not there.

“That happened,” Kosmala says, “long before Maersk went public obnoxiously advising shippers to double up on inventories and import more just in case.”

Eventually carriers started adding capacity back, but by then the backlog was simply too immense to handle.

“Even if the carriers restored the services to 100% right away, it would have taken two years to ship all that backlog mixed with all the regular shipments that were being added at a normal pace,” Kosmala says.

Carriers still went very cautiously about restoring capacity, which simply aggravated the problem and extended the catch-up period, he argues.

Supply chain is not a perfect science

Dr John Gattorna, a Sydney-based global supply chain thought leader and author, argues that there is never a single reason for everything particularly when discussing the supply chain.

The “Covid curveball”, he argues, has exacerbated capacity management issues that were already in existence pre-pandemic.

“Supply chain is not a perfect science and people need to be more flexible in their thinking,” Gattorna argues, advising management to add greater redundancy into their supply chains.

Covid has shown multinationals that they need to give greater thought to shorter supply chains, perhaps at higher costs in order to be more resilient, Gattorna reckons. Speed of decision making will be vital to navigate future curveballs, which we all must accept will be coming our way.

Concluding, CTI’s Lane says, “In this game, it is hard to apportion blame, as it seems that most stakeholders are victims of the circumstances, and all are suffering. Except for the greedy US consumer, it is not really objective to lay the blame on any specific aspect of the door-to-door chain.”

”…..warehouses are so full.” and ”According to Sea-Intelligence research, many industries in the US are actually dangerously low on inventory.”

So which is it? Are the stocks of goods in shortage or surplus?

Or is it being suggested by the expert consultants that both are happening at the same time because of faulty data?

If that is true, why bother talking to the expert consultants at all because they don’t seem to know either!

Kosmala and Gattorna are closer to the reality because there is no single cause and because supply chain not EVEN a science (never mind a perfect one). What has happened is simply the same as a Stock Market stampede as a reaction to instability and rapidly changing conditions (caused by the pandemic). It can take months or years to correct container and ship imbalances even on a single trade lane, never mind in global trade and all the time the liner shipping companies are benefitting hugely as they are the only service providers who can solve the issues created by their own actions and by the actions of others.

The conclusion is really that global sourcing of products is a strain at the best of times because of time and distance. The only reliable way to mitigate that problem is to shorten the distance of supply by near-shoring (but you will never hear that from the lips of a liner shipping exec……..).

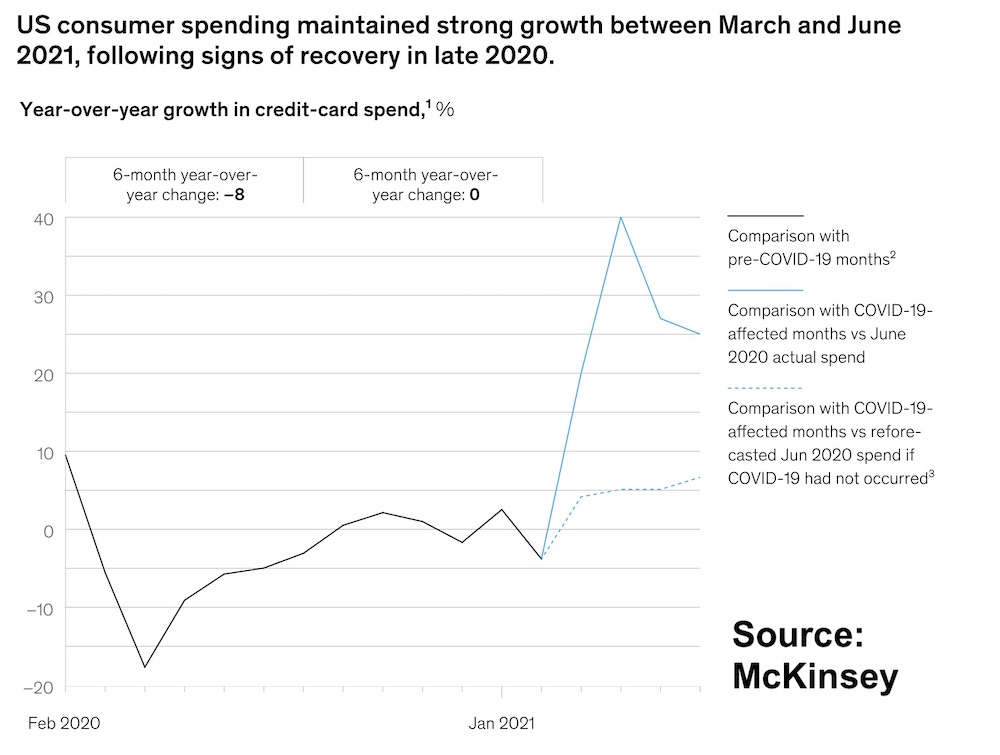

“The greedy US Consumer.” Nice. Try injecting $1 Trillion of stimulus into your economy and let’s see if your consumers are not greedy too. No mention of economic stimulus driving consumer demand is an interesting gap in the article. How is it that US demand is off the charts in the midst of a pandemic? Hmm…

David

You are completely correct

The trillion injected into the us economy – those consumers are not spending that extra cash on food or fuel or rent or dining out

They are shopping online

They are buying stuff they never knew they wanted or needed

The ocean carriers have gone out and chartered every available ship at pretty

High charter rates – they have continued to build and introduce record sized ships

They are buying new containers as fast as they can be manufactured

Consumers have taken the global

Ocean supply chain for granted for 40

Years – carriers never made any sustained profits during those years

I worked in the industry for 45 years and I can tell you – historically

It was not a place to invest – hence

There are no large American shipping lines left – why – shareholders have no appetite for low margins and rollercoaster volatility .

The supply chain will get back in balance by 2023 when new mega ships get delivered – and the us government stops sending Covid che is out to people who don’t need the $

Add to that the Labor shortage caused by the huge unemployment being paid out and you have a perfect storm

Analysis makes a lot of sense. I don’ know the situation on the ground in the USA but panic buying we know can cause major disruption and this may be a lot of panic buying all at once.

The article does assume that players give the slightest consideration to other partners in the chain which i find slightly amusing. Since when did a carrier ever care about a ports capacity for example, they just lean on it until it breaks seems to be the standard ‘MO’ in this area (even pre pandemic there are numerous examples of this).

Are there lessons to learn – absolutely. will the industry learn from these issues? personally i doubt it.

I like your comment and it shows that you actually read the article carefully. I think the article is good, and address at least the right direction toward the issue. The fact that Sam pointed out about Full Warehouses and the stock are empty can be both true, and co-exist; because of different reasons (I don’t have data, rather my assumption):

1. Cargo are delay at all stages of the supplychain. The cargo, in its shape and form, takes space in warehouses but doesn’t mean that it would be on the shelves/in stock for consumer. It would be a perfect example to have full warehouse of toiletpaper but because of chasis and truck shortage; there is no toilet paper in the supermarket.

2. For finished products to be avialable to consumer; it would required Ochestrated of arrivale time of different parts/materials; and the lack of one part might just be the perfect reason for the full warehouse of other parts.

3. Thirdly: the full warehouse of one category such as shoes which has been over ordered and waiting to be cleared; would be a perfect roadblock for the shipment of gloves that is waiting in line; while there is no gloves in stores. (given that there are 100 thousand of other things are being moved to the stores daily for consumers).

4. The mightly shift in consumption. Furniture and House maintainance (bigger volume) is among the most popular imported items to US. Would the shift in the larger/bigger item put stress on warehouse space, fill them up so quick… and take all space of other items

5. Probably not last, is the imbalance stock in the stores. Some stores that have a lot of shoes and boots; but missing matching outfit for the next season. It is crazy but can be true in reality, hence the empty stock.

Warehouse are full yet companies are dangerously low on stock.

This is because deliveries are not being made due to a shortage of labour in delivery. Industrial customers that use these products don’t have the available labour to then process these components into finished products.

There is also the issue that due to the instability of the supply lines, logistics require larger safety stocks. A small amount of extra buffer stocks can greatly effect the warehousing space once it arrives.

Ive been in warehousing for over 20 years in New Zealand and Ive never seen this much unreliability in global supply.

Its an exciting time to watch technology develop along with new stragies companies are having to come up with to survive.

Great article Sam. Even the comments are great. Well Done