New study unveils the mental health ‘minefield’ seafarers face

Whether on or offshore, the work and lifestyle of remote rotational workers, including seafarers, is unique. While lucrative for some, it has long been associated with a high impact on mental health and wellbeing. A new global report from the International SOS Foundation and Affinity Health at Work provides an in depth insight into the psychological impacts of this unique mode of working. The new study highlights evidence of the high level of suicidal thoughts, clinical depression, impacts on physical health such as diet and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on remote rotational workers.

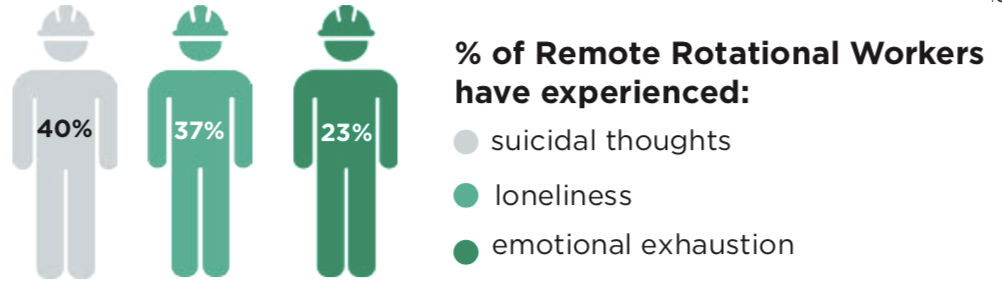

Key study findings show that 40% of all respondents experienced suicidal thoughts on rotation some or all the time compared to an average of 4% to 9%. One in five are feeling suicidal all or most of the time.

29% met the benchmark for clinical depression whilst on-rotation while 52% reported a decline in mood, and their mental health suffered whilst on rotation.

62% had worse mental health than would be the norm in a population. While off rotation, this remains at a high of 31% experiencing lower mental health than the general population.

The study also exposed that almost 23% of the remote rotational workers surveyed experienced emotional exhaustion on a weekly basis. 46% experienced higher stress levels while on rotation and over half – 57% – were not engaged in their work. 23% reported that they received no psychological support from their employers.

Dr Rodrigo Rodriguez-Fernandez, medical director at International SOS, commented, “There is an urgent need for increased focus, understanding and strategies to mitigate mental ill health and promote better metal health of the remote rotational workforce. This is highlighted in our survey, which uncovers significantly high levels of critical mental ill health issues, including suicidal thoughts and depression. The Covid-19 environment has also added increased stress on this already pressured working arrangement.”

The study looked at the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic with 65% of respondents experiencing increased job demands and 56% of those surveyed suffering increased working hours stress and anxiety.

While I believe seafarers from traditional maritime nations would have much less of a percentage of depression and/or suicidal thoughts (pandemic aside) because of their ability to be with love ones and friends more than labor supplying nations. Being a part of your community is important to any human being. Seafarers being expected to work 9-11 months rotations with a few month off prevents one from feeling part of a community. I am curious in the study’s nationality breakdown. Additionally, wages have been stagnant in the industry and this, IMO plays a part in anyone mental health, especially with seafarers. I agree with Dr. Rodrigues’ view, that there must be an increase focus to help mitigate mental ill health in the maritime industry.

The solution to this problem is to remove the circumstances that pitch today’s seamen into suicidal depression. We know what they are. They have been known for decades. Seamen are not a different breed of humanity. We share the same anxieties as people ashore. What has changed is not the seafarer; it is modern shipping that in it’s monotony and isolation has created an environment that is hostile to mental health. Long contracts, small crews, less contact with loved ones, no means of airing grievances, a top-down management style that bears down heavily on the Master, and through him the crew, no union representation, uncertainty of being fully paid, even accommodation that is utilitarian rather than comfortable. I’m sure we could go on adding to the list. This study, like so many others that have gone before, is aimed at making the seafarer fit the job. Obviously shipowners are not going to start redesigning the accommodation, abandoning lucrative trading patterns, and adding crew to prevent isolation. It is what it is. Since Manning has moved out of NW Europe the shipowner can dictate what he wants, and there will always be people willing to take a job to improve their families standard of living.He doesn’t have to care that much about them over and above how much they cost him. So rack this one up with all the other attempts to “cool-out” the seafarer.

I work in a Seafarers’ Centre. Even now during the pandemic we often receive requests from people overseas asking, ‘Can you help me find a job?’

Whatever a crewmember faces on ship, he knows that he has to deal with it himself because there is a long line of people waiting to replace him.

Neutered by ship managers, sailors never will be happy. Unable to fight socially, the sailors feel their virility diminished.

Minimum Safe Manning is the key issue.