Shipyards need to expand to meet IMO green goals: ClassNK

Japanese classification society ClassNK has crunched the numbers to work out the volume of ships yards will have to churn out in order to comply with the indicative checkpoints agreed at this year’s new International Maritime Organization greenhouse gas (GHG) targets. In short, 80m gt of zero-emissions vessels will need to be handled by shipyards – both as newbuilds and retrofits – each year between 2027 and 2040.

The 36-page report analyses the allowable lifecycle GHG emissions for international shipping and the required introduction amount of zero-emission fuels and zero-emission ships to achieve the targets and indicative checkpoints in the 2023 IMO GHG strategy.

In July, IMO members agreed on so-called indicative checkpoints of reducing emissions by at least 20%, and striving for 30%, by 2030 compared to 2008 levels, and at least 70%, striving for 80%, by 2040, reaching net-zero “by or around, i.e., close to 2050” – qualified by whether “national circumstances allow”.

To achieve the indicative checkpoints for 2030 and 2040, approximately 25% then 72% of the fuels used in international shipping must be zero-emission fuels according to ClassNK.

ClassNK estimates it will be necessary to introduce 85m gt of zero-emissions ships annually from 2027 to 2030 through a combination of newbuildings and retrofits. To meet the 2040 targets, an annual introduction of 77m gt of zero-emission ships will be required in the 10-year period from 2031 to 2040.

Given that the 25% introduction of zero-emission fuels is required to achieve the indicative checkpoint for 2030, achieving only a 5% to 10% introduction of zero-emission fuels, as outlined in the 2023 IMO GHG strategy, would make it “challenging” to achieve the indicative checkpoint for 2030, ClassNK suggested.

Even if the indicative checkpoint for 2030 is not achieved, an annual introduction of 80m gt over the 14-year period from 2027 to 2040 will still be necessary, something the class society maintained was entirely possible from a shipyard capacity point of view.

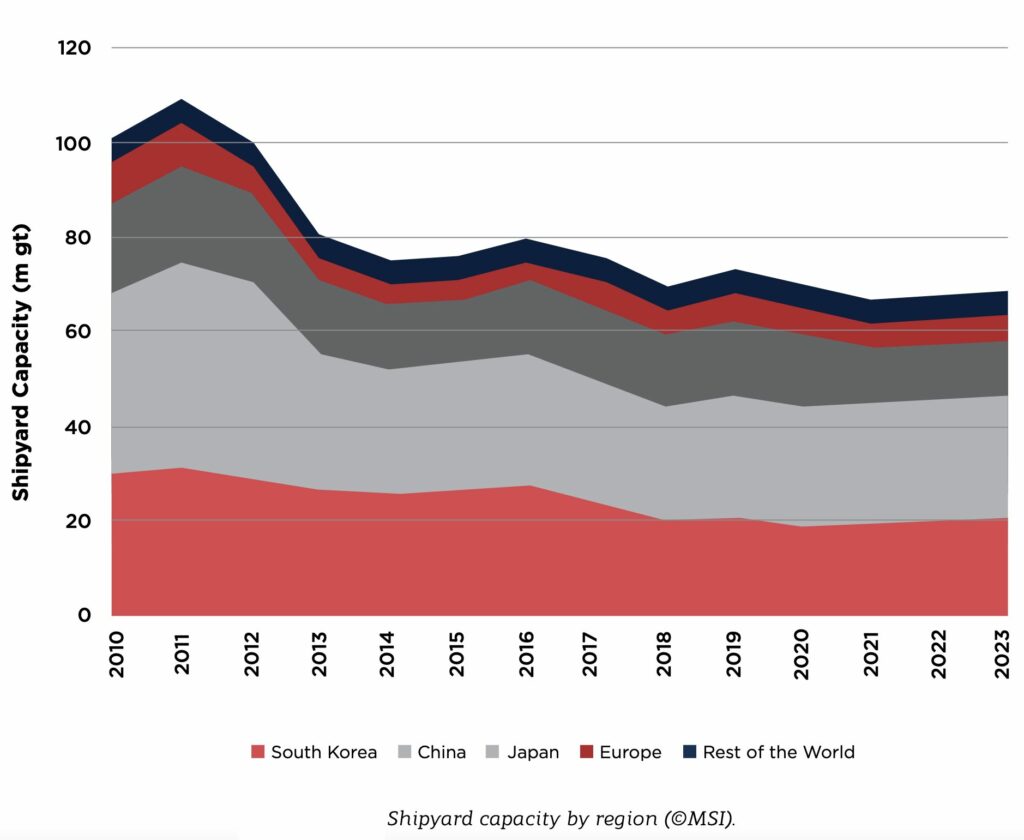

After many years of contracting shipyard capacity, the global yard scene is finally expanding amidst record-long orderbooks, and a growing acceptance that much of today’s fleet will need to be replaced to meet new green regulations.

According to data from Maritime Strategies International (MSI) carried in class society ABS’s recently published 2023 Outlook, shipyard capacity grew 1.8% to 67.1m gt last year with MSI forecasting this figure will rise to 69m gt by 2025, and will peak at 81m gt in 2030 (see chart below). While this is significantly above current levels, it remains 26% below the 2011 peak.

The Review of Maritime Transport 2023 published by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) last month urged shipyards to expand quickly to aid with shipping’s green transition.

“Shipyard capacity is currently facing constraints. Tanker and dry bulk owners are anticipating long waiting times and high building prices. Increasing shipbuilding capacity is crucial to ensure that shipping meets global demand and its sustainability goals,” the UNCTAD report stated.

Looking at repair yard capacity rather than newbuilds, class society Lloyd’s Register (LR) has just published an engine retrofit report in which it argues a lack of yard capacity and capability could compromise the maritime industry’s retrofit ambitions.

A maximum addressable retrofit market of 9,000 to 12,900 large merchant vessels was identified up to 2030 in the report, after which it is anticipated that all vessels will be built with net-zero or near-zero carbon fuels capability.

“In all likelihood, only a small number of these vessels will eventually be retrofitted as the business case for converting older vessels (beyond ten years) and smaller vessels will likely remain challenging,” the report noted.

Fuel retrofits are more complex than most projects undertaken by repair yards, the study made clear. Converting the engine itself is a relatively straightforward process of installing prefabricated engine components.

“Introducing these elements to an existing ship, designed with an entirely different fuel use in mind, requires skills that cannot always be taken for granted at repair yards, where the focus has traditionally been on restoring vessels based on an original design,” the report pointed out.

LR has identified a group of around 15 yards capable of handling alternative fuel retrofits. Allowing a 60-day conversion period, these yards could be capable of handling up to 308 conversions in total each year.

“Comparing this against the number of potential retrofit candidates for methanol and ammonia, it is clear that capacity would need to be increased dramatically to fulfil potential demand as interest in conversions increases,” the report stated.

Another factor for consideration in understanding the capacity for retrofit projects is slot availability in repair yards. Repair capacity is already constrained, according to LR, while the authors of the report warned there were other constraints on the supply chain with engine builders needing to balance the demand for newbuild engines with the growing demand for engine retrofit packages.

But to be clear, Maersk’s efforts are much more virtuous than Methanex’ Atlantic crossing by a ship powered by purportedly green methanol that was actually 96% fossil natural gas derived. That was some of the most egregious greenwashing I’ve seen in the space. But how virtuous is ensuring that some of methanol in circulation is green?

Job one for major climate problems is to fix the emissions of the current products or reduce the use of them, not multiply demand for them.

https://cleantechnica.com/2023/10/13/maersk-green-methanol-plans-wont-decarbonize-methanol-much/

The implications for all of this on freight rates seems to be the elephant in the room.

Increase in operating costs by up to 600 percent The calculations that ETH makes in precisely these contexts are quite something. It is said here that operating costs increase by up to 600 percent, while transport performance decreases exponentially in return. https://www.n-tv.de/auto/Der-teure-Weg-zur-klimaneutralen-Schifffahrt-article23069139.html

https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-how-low-sulphur-shipping-rules-are-affecting-global-warming/