Storm-hit Maersk Essen reroutes to Mexico

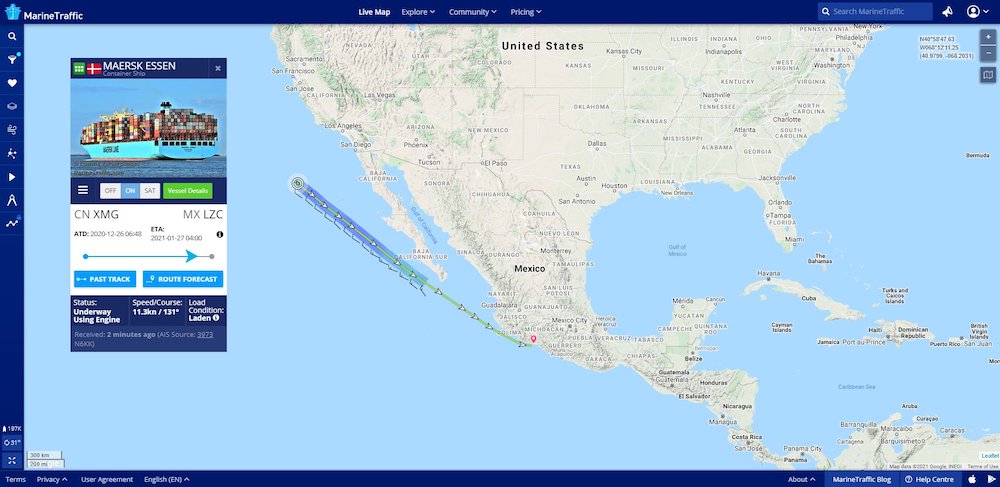

The 13,100 teu Maersk Essen boxship has rerouted to Mexico instead of its intended destination of Los Angeles.

The ship became the latest boxship to suffer a container spill on the Pacific, losing up to 750 boxes on January 16 in a storm. The Maersk accident was the fourth box spill in the Pacific in the space of just 47 days with nearly 3,000 containers lost in the world’s largest ocean since November 30.

The ship, which was due to call at Los Angeles from Asia today, is now heading south, bound for the Port of Lázaro Cárdenas where sister company APM Terminals has a concession. The vessel is expected to spend some time along side taking off damaged boxes on deck. It will also be surveyed for repairs.

With the extreme current port congestion in California, and then huge costs to remedy the container mess onboard the Maersk Essen, continuing to Los Angeles did not make sense. The Mexican contingency offers available capacity, lower costs and less bureaucracy.

Looking into the increasing cases of lost containers at sea, the Standard Club, a P&I club, issued a recent report. Looking specifically at the latest generation of megamax boxships, the club noted the large beams of these 23,000+ teu giants result in them having relatively large metacentric heights (GM), meaning the vessels are very stable and therefore stiff. This in turn can result in very high rolling accelerations when the weather deteriorates, generating similarly high loads in the container lashing and securing gear.

Increasing commercial pressures mean that containerships usually have to keep to very tight operating schedules and they need to be as fully loaded as possible

“Increasing commercial pressures means that containerships usually have to keep to very tight operating schedules, particularly in the liner trade, and they need to be as fully loaded as possible. As a result, they have increasingly powerful engines, not only to provide the high speeds required but also to enable speed to be maintained during bad weather,” the insurance firm pointed out.

The consequence is that, at times, containerships can be driven hard. When ships are driven hard in bad weather, the loads on the container lashing and securing gear can be severe.

Almost all container stack collapses at sea occur in rough weather with strong winds, the club noted. When fully loaded, the deck stacks on modern containerships present additional windage areas over 25 m high. Combined with large freeboards, the stacks act like giant sails to amplify a ship’s motions as the weather deteriorates, further adding to lashing and securing loads.

The report went on to discuss parametric rolling, a phenomenon where sudden heavy rolling occurs in head or following seas. Although very rare, it tends to affect vessels such as containerships which have large bow and stern flares. Parametric rolling can trigger violent rolling of over 30° in a very short period of time. Such violent rolling can lead to extreme loads on container lashing and securing gear.

For beam and quarter waves, if a containership’s natural roll period synchronises with the experienced wave period, resonance can occur resulting in similarly violent rolling motions.

Larger, stiffer container vessels tend to have shorter natural roll periods that more closely match the periods of the wave spectrum. This in turn increases the risk of synchronous rolling and over-loaded container lashing and securing gear.

Issues relating to parametric rolling and big boxships were also discussed in a recent paper from the Busan-based Journal of Ocean Engineering and Technology.

With the current extraordinary demand – and sky high freight rates – ships are crossing the Pacific with very high utilisation rates.

The paper carried in the Korean journal suggested that the latest generation of megamaxes could face stability issues with the authors urging they travel with less onboard cargo or at slower speeds.

Returning to the report from the Standard Club, which also looked at improper container stowage. The stack weight on a containership is the total weight of all containers and their contents in the tiers of a particular stack added together. The ship’s cargo securing manual states the maximum permissible stack weight for each stack. Deck stack collapses often occur in those bays where the stack weight was exceeded.

Furthermore, the distribution of weights in a container stack directly affects a vessel’s stability. The cargo securing manual specifies a maximum permissible GM for the vessel to avoid excessively short rolling periods and high accelerations. It is therefore important to get the GM within the right range before a voyage starts to avoid overloading lashing and securing gear.

The Standard Club then went on to discuss issues arising from overweight, poorly packed and/or structurally weak containers, all of which can lead to stack collapses.

Another issue discussed was the lashing of containers, something that has become problematic as boxships have nearly quadrupled in capacity this century.

Containers are basically secured to each other with twistlocks fitted at their four corners. Lashing rods and turnbuckles are then used to secure the container stacks to the deck by connecting them to the hatch covers, deck posts or lashing bridges if fitted.

However, lashing rods are only able to reach to the bottom of the third tier of containers loaded on hatch covers or deck posts, or to the bottom of the fourth or fifth tier of containers where a lashing bridge is fitted. This means that on large modern container ships, several upper tiers are secured by twistlocks only.

For the deck stowage system to be effective, the lashing and securing gear needs to be fitted correctly. Missing twistlocks, unlocked twistlocks, damaged lashing gear and lashings becoming lose in a seaway are examples of inadequate securing which can lead to a container stack collapse.

In a comment sent to Splash yesterday Dr Henry Chen, a retired naval architect, suggested urgent mitigating strategies were needed or else similar accidents will continue to occur.

“The reason why we don’t see many similar accidents in previous years is because most of these large containerships were lightly loaded due to lack of cargo. Now these ships are fully loaded. Parametric roll resonance comes into play when the large bow flares are immersed in waves due to ship motions,” Chen wrote.

boxship has rerouted to Mexico instead of its intended destination of Los Angeles.

boxship has rerouted to Mexico instead of its intended destination of Los Angeles.

It’s harder for the cargo lawyers to get a subpoena in Mexico, particularly at an APM terminal, also.

Thirty six years ago, when working for – coincidentally – the Standard P&I Club, I arranged for the entire crew of the OCL container ship “Falmouth Bay” to be relieved at their port of refuge – Yokohama – before the ship resumed her voyage to Los Angeles after mislaying 100 boxes on the same passage – she was all of 1,200 TEU.

They gave their evidence all right – a year later in New York, when they had had time to think about it.

There are 40+ ships in LA/LB Anchorage awaiting a berth. Not surprising they bypassed this port. Mexico has “other advantages” of course. But smart call to get ship fixed and back to work.

Mr.. S.C.

I am truly impressed. Written, like by an old salt and sea dog captain from container ships and very accurate references. So i do remain speechless.

Most efficient measure is to start fitting large container ships with hydraulic fin stabilizers in order to reduce rolling in rough seas.

I used to sail on this kind of ships built in the 80’s at St Nazaire and it was a huge difference.

Could be we sailed on the same ships. Does Kazimierz Pulaski , Stefan Starzynskii , Tadeusz Kosciuszko, ring the bell? 1983- 1989 G.A.L. service BRH- ECUSA.