Supply, not demand key to container sector’s ability to fight coronavirus

In the second part of his analysis, Dr Adam Kent, managing director, MSI examines the risks to the container market posed by the virus.

The impact of the coronavirus on the Chinese economy has already been severe and the scenarios for shipping range from a quick resolution to a long drawn out impact. In modelling the likely effects, MSI has analysed how the virus is affecting shipping sectors now and what the future implications of a further escalation might be.

Each sector has been affected to a different degree by the crisis so far, and each has a different set of vulnerabilities to escalation or prolonged disruption.

The impact on the container trades has been different to that felt in the dry bulk and tanker sectors, with relatively small movements in markets so far but major disruption to trade. However, the downside risks from escalation and further disruption are similarly extensive.

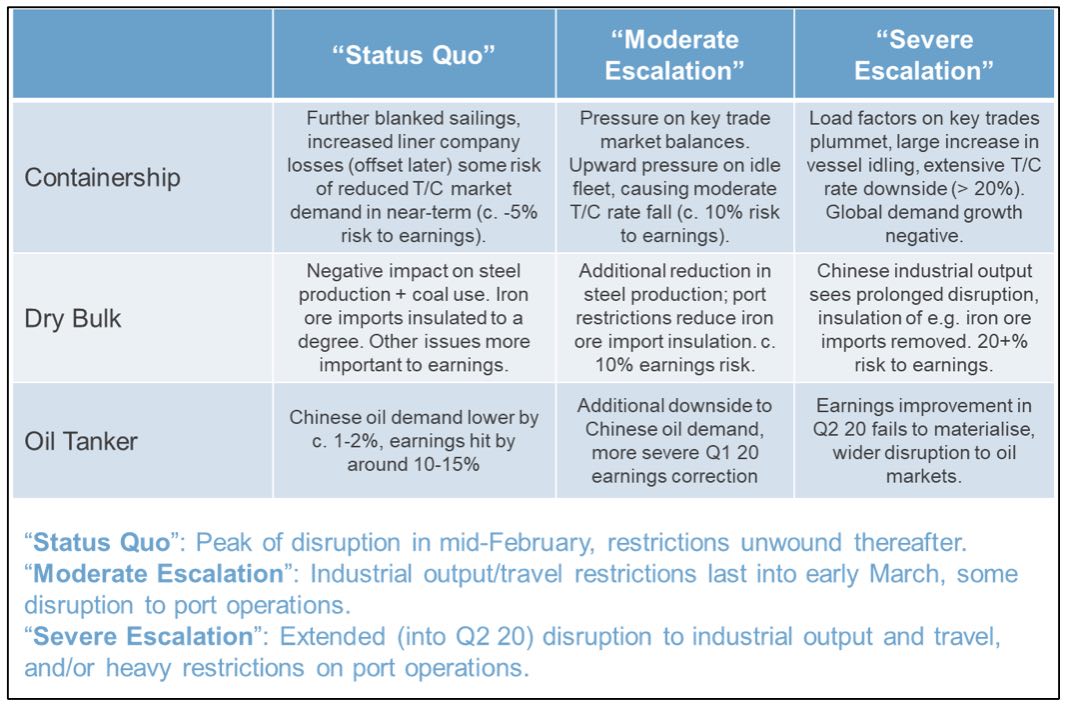

The MSI risk matrix depicts how different segments will be affected by the status quo in which we expect that the disruption peaks over mid or late February and then restrictions to output and mobility are unwound thereafter.

We add a moderate escalation scenario in which disruption continues into March and there’s some restriction on port activity over that period of time, which again implies further downside risk to vessel earnings.

Lastly we model a severe escalation scenario in which the impacts last well into Q2 forcing a continued shutdown or increased shutdown of Chinese factory output or significant disruption to Chinese port operations. In that case the market should expect double-digit downside risk to vessel earnings in the different segments.

Containers ride the storm

The container shipping sector has experienced a different type of exposure to the coronavirus, with the immediate impact on markets so far arguably the smallest among the three main sectors. Disruption to containerised supply-chains and liner company operations has been extensive, however, and the longer this lasts, the less markets will be insulated.

For containerships, the coronavirus is fundamentally a question of supply not demand, as disruption to China’s manufacturing output and port operations effectively creates a big reduction in the supply of containerised goods. The impact so far effectively amounts to an extension of the Lunar New Year – when even in normal years container trade flows take a hit, freight rates tumble, and factory output takes weeks to return to normal.

The coronavirus has turbo-charged these normal seasonal trends. The result is that Chinese factories are operating far below capacity, and with few boxes to load liner companies have implemented an increased programme of blanked sailings.

Our view is that provided that workers do return to factories in around mid-February onwards and disruption to port operations outside Wuhan are contained, the impacts on long haul container beyond mid-March will be relatively limited.

The impact is going to be larger on the intra-Asia trades where demand growth will slow significantly in the first quarter of this year. This of course applies to Chinese domestic trades, but also to trades where Chinese exports to foreign manufacturers play a key role. There is already evidence this is limiting liner company demand for extra tonnage in East Asia, with downside implications for timecharter earnings in the near-term.

The key question for containerships is how far the situation escalates. If we see significant disruption to Chinese manufacturing operations beyond the next several weeks, or the start of significant port disruption if the return to work actually worsens the outbreak, the downside for containership demand out of China could become severe in its implications.

MSI has modelled three scenarios. The first is a Base Case in which most Chinese businesses are back to work within the next week or two and there are no major disruptions to port operations. This leads to a slightly lower view of global container demand compared to our pre-coronavirus Base Case.

Then there is a moderate escalation scenario where the disruption to factory operations extends into the middle of March. This could lower headhaul global demand growth by about half a percentage point in 2020.

The third is a severe escalation scenario in which Chinese export volumes in Q1 20 are 50% lower than our Base Case on the key trades and 30% lower in Q2, prompted by either massive factory closures or significant disruptions at the main ports.

We would expect this to result in negative headhaul demand growth of about minus 1% in 2020.

So far, there has not been a massive impact on the spot freight rates that drive liner company profits, at least beyond normal seasonal trends. However, the impact of an escalation will first be felt in the container segment through spot freight rates, and absent a freight rate recovery this will impair balance sheets at a time that industry fuel expenditure has risen.

Demand for time charter tonnage in the container segment is a derivative of container demand so the longer the disruption goes on, the more likely it is that liner companies will consider redelivering vessels at the earliest possible date or refrain from taking on new tonnage. It’s likely that some of that impact will be felt soon, and certainly within the Far East that there is going to be an increase in the idle fleet of smaller containerships in particular as liner companies take a cautious approach taking on new tonnage.

As with the other sectors, the downside risk for containership freight and charter earnings lie in further escalations; if companies to start to lose significant amounts of money then tonnage demand will be scaled back until demand and supply recover towards something approaching full health.