Short term sunshine, longer term rain?

The shipping market is emerging into an upward trend cycle but is ever more impacted by external factors, argues Adam Kent from Maritime Strategies International.

Despite appearances to the contrary, 2018 wasn’t too bad a year for shipping. Seaborne cargo growth for all the major sectors was positive while supply side fleet growth was in some cases negative but generally low. That was good for supply/demand side balances with the exception of LNG, where we saw both strong supply growth but at the same time strong seaborne cargo growth.

However it’s unexceptional to observe that the future looks more complicated than the past. The observation might not be new but the extent to which structural changes are re-shaping the shipping market is perhaps not as widely understood as it should be. In 2019 and particularly from 2020 onwards it should become clearer where the short and long term risks lie.

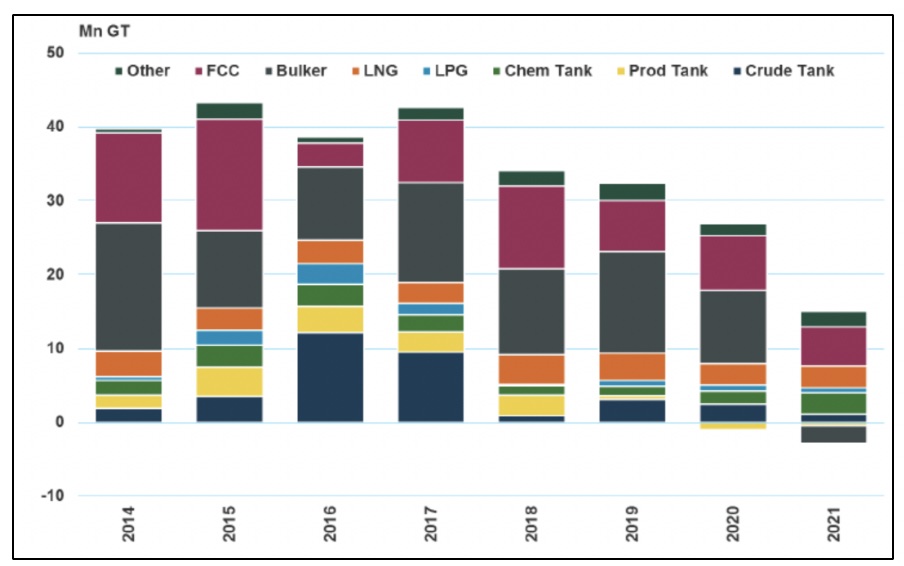

Slow fleet growth is certainly one bright spot; in the last three years we’ve seen contracting as a percentage of the fleet under 5% for the first time since the 1980s. Factoring in slippage and cancellations against new contracting and scrapping, by 2021 we’re starting to see negative fleet growth in a number of key sectors.

Chart 1: Net Fleet Growth by Sector

One of the drivers to controlling fleet growth is consolidation. Consolidations typically happens as the markets come out of a trough and into an upward trending market – though in the containership market the very short sharp cycle of 2016 and 2017 meant that some of this consolidation took place in a downward cycle.

In general, as we’re entering an improving market across a number of sectors of shipping we will start seeing more consolidation; a similar dynamic has also been seen in the offshore sector.

Plotting the oil price against offshore consolidation it typically takes place in upward trending earnings environments, suggesting there could be more to come.

Performing a simple SWOT analysis across the main shipping sectors identifies policy as a major driver across the board. Whether it’s OPEC and the tanker market, the Chinese government and dry bulk or wider trade wars on the container side, policy now is one of the factors that the industry is having to deal with which could dislocate any continued momentum on the upward part of the earnings cycle.

In the tanker sector in particular, the biggest impact in the next three or four years will be the tug of war between OPEC countries and North American oil production. US production is winning that tug of war; since mid-2017 we’ve seen month on month US production outweighing Middle Eastern growth or in some cases Middle Eastern cut backs, which are set to increase further.

The US is going to continue to win that battle. If we look out towards 2022, the US and Americas, as a whole will continue to add more production to the oil markets. By 2022, 28% of global crude exports will emanate from the Americas, a good story for tonne-mile balances.

The longer term risk to this and other market sectors is the decarbonisation of shipping. It’s a subject that MSI are being asked to look at more frequently by owners, classification societies and NGOs and we’ve been considering it both from decarbonisation of shipping and the decarbonisation of the global economy more broadly.

Looking at some of the trade scenarios that are already in play – the ones that industries other than shipping are looking at – it’s clear decarbonisation will have huge ramifications on shipping. We have analysed the potential impact across a number of trade scenarios and the results suggest there could be a very significant results on the requirements for shipping demand out to 2050.

Chart 2: Global Decarbonisation Extreme Scenario – Impact on Shipping Demand

Of course the underlying impact of decarbonisation is very much dependent on which cargo is being considered. Changes to individual country production and consumption dynamics will hit some bilateral trade routes harder than others. For chemical and grain commodities it’s almost business as usual from a shipping standpoint, but obviously for a lot of the hydrocarbon cargoes it has huge implications.

Shipping is an industry where assets last 20, 25 or even 30 years plus, so even by 2035, based on some of the more extreme scenarios, there are huge consequences to the industry and given the timeframes these need to be considered and planned for today.

How engaged the shipping industry really is to this challenge remains to be seen. There is a certainly a lot of talk about clean technologies but whether the long term and lasting impact is anywhere near being fully understood is still open to question.