Search resumes as final moments emerge of stricken livestock carrier off Japan

The Japanese Coast Guard resumed aerial search operations for missing crewmembers of the Gulf Livestock 1 today after a typhoon-hit weekend made search and rescue operations impossible.

Forty crew are still missing from the ship, a converted boxship, which lost power, took on water, capsized and sank with more than 5,800 cattle onboard. Two crew have been found alive so far, and another was found unconscious and pronounced dead on arrival at a Japanese hospital.

Photos have emerged showing water pouring into the Gulf Navigation ship shortly before it sank (see above).

The captain of Gulf Livestock 1, Dante Addug, 34, texted his partner saying he was praying during the moments leading up to the ship capsizing, after it sailed into a powerful typhoon.

“The typhoon is so strong up to now. Here I am praying for the typhoon to stop,” Addug texted.

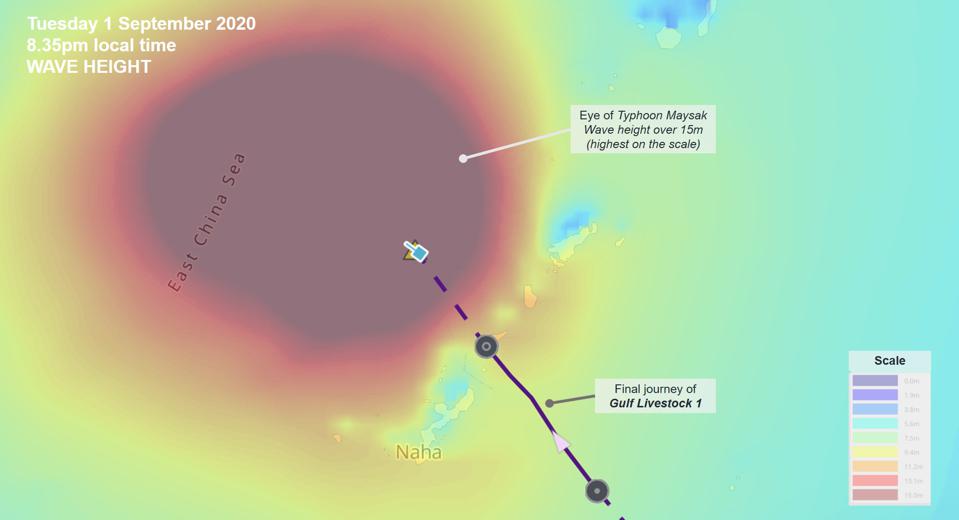

Data provider Windward has provided a track of the last miles of the Panama-flagged ship’s voyage in the East China Sea (see below) as it headed into the centre of the typhoon with waves likely in excess of 15 m in height.

UAE-based Gulf Navigation, which has just shuffled top management in the days following the accident, has another two livestock carriers in its fleet – one built in 1973 and converted 10 years later, and another built 35 years ago and converted in 2014. The Gulf Livestock 1 started its trading career as a 630 teu containership in 2002 before being converted to carry animals 10 years later.

today after a typhoon-hit weekend made search and rescue operations impossible.

today after a typhoon-hit weekend made search and rescue operations impossible.

It seems incredulous (but sadly, it is not) that a small, vulnerable ship like that is anywhere near a typhoon, especially when laden

Was any avoidence of the centre of the cyclone done ????

Good stability is the best and only defense against any typhoon.

This wretched ship had not such defenses and we all know why. All is out there, published in the press and AMSA reports

The best defence against a typhoon is to stay as far away from it as you possibly can, and the measures to bring this about are well documented. That they do not appear to have been followed brought about this tragedy, and there are at least echoes of the loss of the El Faro.

How on earth in year 2020 you sail straight in a typhoon.

What happed to weather updates, navtex, Internet.

Weather forecasts are even broadcasted over MF/HF which exists on every ship crossing an ocean.

Some serious questions on the ISM compliance of that company.

Yes, right back to the origin of the cargo. Why was this voyage attempted in hurricane season, when a wait of a month would have reduced the risk considerably?

Because if the Filipino captain didn’t sail the vessel, most likely he would have been replaced by another Filipino captain who would have sailed the vessel into the typhoon anyway.

Filipino officers are trained at the their maritime college to always say “yes sir”, not challenge one another and smile when they do something wrong. Common sense: gone. Challenging each other on the bridge: gone. Challenging the company: gone.

If anyone can tell me that I’m wrong, please, I’m all ears.

That plus there area whole host of technical issues relating to centre of gravity being too high to sail through the rough seas. That’s suicidal – no question.

Predicting a typhoon is not possible. No current technology is capable of predicting a path for a typhoon.

The stability calculation of a livestock vessel is extremely hard even using all that modern technolgy has to offer.

Primarily because it is a very unstable cargo. When the ship rolls in a heavy weather, unlike human, livestock takes much longer time to recover balance. They usually stay stuck to one side of the vessel thus making a huge problem to correct gravitational force against the heavy seas which is why there is a high tendency to capsize. Container ships do have similar problems but cargo would generally break loose from its securing if the weather is that extreme, whereas livestock cannot escape from its caging so, the probably is that it went down locked inside their cages sadly.

I guess the question is one of prudency and commonsense.

Sailing a livestock vessel (which has previous bad records of maintenance issues) into the eye of the typhoon is sucidal from any perspective. Quite commonly, Middle Eastern and Asian ship charterers tend to give an attractive bonus to ship captains and chief engineers

for either carrying a little more cargo (assuming it will be at a perfect draft upon arrival given consumption enroute) or take a little more risk to cut corners for them ignoring safety and commonsense and welfare for the crew.